Abstract

Design Sprint, a method where business ideas are tested in just five days, has been adopted as a method for all the students to learn on Porvoo campus of Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences. The method incorporates the 21st century skills: collaboration, communication, creativity, complex problem-solving and critical thinking. Due to the pandemic, 130 students from four different degree programmes joined 7 supervisors online to complete the week-long sprint during the autumn semester 2020. The online environment brought along different challenges and opportunities.

The objective of the study was to analyse how well the remote Design Sprint serves the purpose of learning the 21st century skills and compare experiences of the first remote sprint on Porvoo campus with previous five face-to-face implementations. The aim was also to study what participants learn and how future sprints can be improved.

The data collection was based on the written feedback given by the students and the observations of the supervisors taking part in the sprints. Students found the sprint an emotional but exciting ride where they learnt digital collaboration tools along with the 21st century skills. Supervisors learnt new online skills and were surprised that the first remote sprint worked out so well. Even more emphasis on how to engage students online can be added to future implementations.

Keywords: Design Sprint, online learning, pedagogical methods, 21st century skills

1. Introduction

It already seems certain that online learning is here to stay in the post-pandemic world. Besides mastering technology and tools for collaboration and communication, it is also important to learn 21st century skills to thrive in the future world of work. Design Sprint is a method for the future skills, and it has been an integral part of studies for all students on Porvoo campus of Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences. Due to COVID-19, the remote sprint was tested for the first time in October 2020 with 130 students and 7 facilitators. The 5-day sprint was conducted over Zoom and teams collaborated in breakout rooms. Design Sprint is a concept that works well for higher education as well as for businesses. The concept is widely used by companies to develop products and services in a short time. Besides learning a useful tool, for both online and face-to-face work, the students also become acquainted with 21st century skills. Thus, it is both a business tool and a pedagogical method.

The aim of the study is to find out how the first remote sprint on Porvoo campus succeeded compared with the previous face-to-face implementations. Design Sprint is a method which generally works extremely well for learning the 21st century skills and, thus, it is of interest to find out whether the method works in a similar way in the remote format. Online sprints will most likely take place in the future, and it is vital to know what works well and what still needs improvement. The feedback and improvement suggestions by students and supervisors are tracked after each sprint. Indeed, so far, Design Sprint has been a useful tool for learning and bringing students from different degree programmes together. It is interesting to discover if the different formats of implementations affect student learning.

Many businesses and universities of applied sciences use the Design Sprint method, so it is the sincere hope of the authors that the experiences gathered in this applied research paper about the remote sprint are of interest and might offer some practical ideas to a wider audience.

2. Research background

While there are several business cases documented about the Design Sprint (Sprint Stories, 2021) and studies about how to foster innovation through the method in companies (e.g., Magistretti et al., 2020), there is still scant research about its use in higher education (e.g., Gudmunds, 2018; Toda et al., 2019). Further, there is marginal educational research about how students at universities and in adult education (Iñiguez-Berrozpe & Boeren, 2019; Silber et al., 2019) can learn about the 21st century skills. Our contribution sheds light on these two topics through our study about the method and its online implementation.

Many of the studies about learning the 21st century skills focus on digital literacy competences (Silber et al., 2019) or learning through technology (Latorre-Cosculluela et al., 2021; Yoo, 2021). There is a lack of research on the educational methodology and pedagogics of learning about the future skills. A notable exception is Latorre-Cosculluela et al. (2021), who have studied how the flipped classroom method can be used to learn the 21st century skills. While the role of technology is important, our contribution to the discussion is to show how future skills, the so-called-soft skills, can be obtained through the method of Design Sprint, even in an online environment. The study pivots on the method and pedagogics, not the e-learning environment or technology as such. The technology is rather seen as an enabler of learning in an online setting.

Our research focuses on learning the 21st century skills through the Design Sprint method, so in the following, the 21st century skills are presented along with the Design Sprint method and its implementation. Also, a pedagogical manuscript for online learning is introduced as the implementations of both the remote and face-to-face format are under continuous development.

2.1 21st century skills – vital for future employability

The 21st century skills, collaboration, communication, creativity, critical thinking and complex problem-solving are the most sought-after competences in the future of work. They are often also called employability skills (Isacsson et al., 2020). They are soft skills that enable continuous learning and survival in the 21st century (WEF, 2020), the skills that separate humans from machines. OECD (2018) also highlights competences such as empathy, trust, resilience, curiosity, proactiveness, responsibility and self-management as essential for employees to thrive in the future. Schools have an important role in cultivating these skills and competences in students.

World Economic Forum, WEF, (2020) and McKinsey (2021) predict that the “double disruption” of COVID-19 along with automation means that there will be millions of jobs lost. Although the gains in “jobs of tomorrow” will outnumber those lost, the increased labour market polarisation, with growing employment in high-income cognitive jobs and unemployment in low-income manual jobs lost to machines, means that people will need to acquire new skills to be employable (Frey & Osborne, 2013). Identities tied to professions might become problematic as jobs change. It is better to build personal and professional identities on competences, rather than on professions that might disappear (Pölönen, 2020). Many technology companies, such as Google, have been hiring people for years based on their problem-solving skills, curiosity and perseverance, not based on their ability to memorise facts and information (Canton, 2015). Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) need to rethink their offering and focus on competences to prepare their students to the future so that they can transfer skills and knowledge to diverse contexts in an ever-changing world (Grant, 2021; Canton, 2015; Latorre-Cosculluela et al., 2021; Schmidt & Cohen, 2014.)

The skills gap is going to be huge, and companies need to upskill and reskill their workforce continuously. HEIs will continue offering degree programmes that include future skills, but they should also start targeting companies with shorter courses and training, which OECD (2020) considers essential for keeping up with upskilling and closing the skills gap for the future.

According to McKinsey (2021), Zoom and Teams have changed remote work and education permanently. The future of work has already arrived and there is no return to the old normal. Rather, we need to embrace the post-pandemic new normal where we face a significant increase in remote work and online presence. Learning new ways to collaborate and work together will be essential. That is also where the Design Sprint concept comes in as a tool that can transform itself to a remote format.

2.2 Design Sprint – a method for future skills

Design Sprint was developed by Google Ventures (GV, 2019) to help companies design products and services, test prototypes and get customer feedback for their ideas in just a few days. It means that companies can find out soon whether new concepts are viable, instead of spending months on expensive development. Design Sprint is also an innovative learning method for the 21st century skills of collaboration, critical thinking, complex problem-solving, creativity and communication (Konttinen & Moilanen, 2019). Already prior to the pandemic, there were guidelines for conducting the sprint remotely (Knapp et al., 2020). Technology has improved over the past few years and there are now more possibilities for conducting sprints in a remote format: video-conferencing software and virtual whiteboards have become game-changers and enablers for remote sprints – both for HEIs and companies.

On Haaga-Helia Porvoo campus, all third semester students take part in a week-long Design Sprint, which is the content of their Learning Camp 3 module (5 ECTS). Usually, there are 80–140 students, divided into teams of 7 students. There are 14 to 20 teams in each sprint, depending on the size of the semester intake. They are supervised by facilitators who coach the students step by step through the sprint process. After three years of sprints, once every semester, all in all 12 supervisors have become acquainted with facilitating the sprint process. There is teaching material available, and each new supervisor gets assistance and support from more experienced ones. The supervisors work as a team and share responsibilities for all the sprint days. They also coach groups of their own. The sprint is carried out in English. The basis of everything is the Sprint book (Knapp et al., 2016), which contains very detailed instructions for conducting a sprint, as does the Sprint (GV, 2019) website. In company Design Sprints, people from different departments are mixed in the same team to get creative input and diverse points of view. In a HEI setting, such cross-pollination can be achieved by teaming students from different degree programmes.

Students prepare for the sprint by completing a pre-assignment which familiarises them with the sprint concept. Facilitators have devised a detailed guideline for each sprint day. The whole group meets in the beginning and middle of each day, and the rest of the time students spend with their team. The sprint week is very intense and requires focusing on the task at hand from 9 am till 4 pm for five days, for both the students and supervisors. The official sprint is over in a week, but since the educational elements require more time for reflection and customer feedback, there are a few more meetings and coaching for the students.

There are always tools to aid the sprint process and during the remote sprint technological solutions were also used for collaboration. The communication platforms were decided by the supervisor team. Usually, students meet in classrooms and meeting rooms on campus. During the remote sprint, Zoom was used as a platform for the main sprint sessions. For group work, students met either in Zoom breakout rooms or in Teams, which was the platform for student collaboration and file sharing. Usually, whiteboards and flipcharts with post-it notes are provided. During the remote sprint, the interactive and visual collaboration platform Flinga was used as a whiteboard. Prototypes are created with app programmes, cardboard boxes or Legos during regular sprints. Now prototypes were created in Weebly, Wix and Canva. The chat functions in Zoom and Teams were used as a tool for communication during the sessions.

2.3 Pedagogical manuscript – How do the students learn?

Haaga-Helia’s (2021) mission is to open doors to future careers and the school is proud of the high employability of its graduates. During their studies, students are encouraged to find suitable learning strategies, e.g., by taking a VARK test (VARK Learn Limited, 2021) and they get used to tools and technologies used in workplaces. They are work-ready when they graduate. Many degree programmes in Haaga-Helia use Design Sprint based methods. On Porvoo campus the method is used to bring all the degree programmes together to collaborate and innovate.

Haaga-Helia Porvoo has implemented inquiry learning as its pedagogical strategy for over a decade. The authors (Konttinen & Moilanen, 2015) carried out their study of PBL (problem-based-learning) as a method of inquiry learning on Porvoo campus and since then the methods and applications have multiplied. There is a learning culture among the supervisors to constantly develop and explore new methods. However, the foundation of it all, inquiry learning, has remained the same over the years.

Hakkarainen et al. (2004) argue that inquiry learning provides students with a possibility to take responsibility for their own learning, while giving them a chance to construct new knowledge by tackling and solving authentic real-world problems. Students learn to integrate content from different contexts while also learning other important skills and competences during the process. Inquiry learning is a student-centred method where learning takes place in large activities and projects. The current curriculum is based on competences (Konttinen & Sivonen, 2018) such as personal growth competences (e.g., goal orientation and problem-solving), business and entrepreneurial competences (e.g., pitching skills and entrepreneurial thinking) as well as sales and service competences (e.g., customer understanding and negotiation skills). Projects are carried out together with companies, student and supervisor teams. The students need to take responsibility for their own learning, make use of and develop other people’s competences and thoughts, share their knowledge with others, search, assess and compare information available in different sources. These methods give students competences that they need in their future workplaces, where stepping outside of comfort zones, tolerating uncertainty and getting used to constant change will be the norm. Supervisors are co-learners and guide the learning process as facilitators and coaches. In inquiry learning, observation, reflection, assessment and development are emphasised throughout the process. Inquiry learning is a learning style where future skills, such as complex problem-solving and collaboration are learned (Ritalahti, 2015). That is why it is of crucial importance that when designing online and blended learning, the elements of student-centred approach and inquiry learning are not lost.

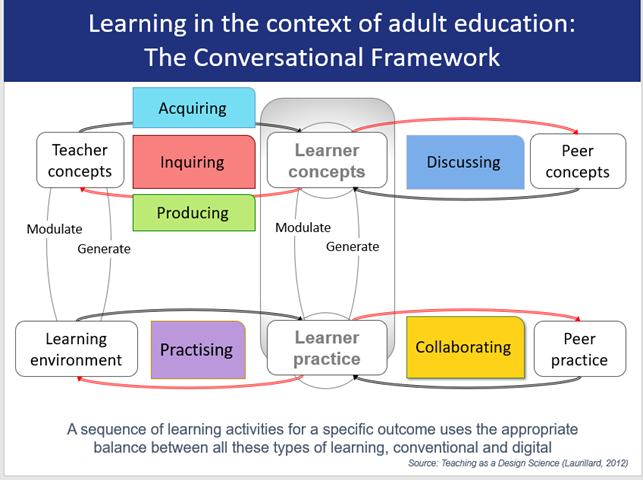

Thus, when designing and assessing the first remote Design Sprint, the ABC model was looked at. The model is widely used in European tertiary education and beyond (ABC Learning Design, 2020) and adopted in Haaga-Helia (Alanko-Turunen & Pietilä, 2021). The ABC model is based on the six learning types “Conversational Framework model of adult learning” by Laurillard (2012) (Figure 1) and further developed by Young and Perovic (2020). It offers resources and methods for various kinds of leaners and emphasises collaboration.

During the remote sprint, all the elements of ABC learning types are present (Figures 1 & 2): Orientation/tuning-in (in the form of icebreakers, getting to know exercises – selfie sketch); Acquisition, i.e., to read/watch/listen (listen/watch the commission, videos, inspirational talks, studying for the pre-assignment before the sprint); Production (Crazy 8, solution sketches); Collaboration (designing a prototype); Discussion (presentation and feedback, testing their prototypes/interview questions with peers); Practice: students receive feedback from each other, supervisors and most importantly from the potential customers which helps them to develop their concepts further and improve their presentations; Investigation (Inquiring) (online search, benchmarking – lightning demos). All types of learning were present many times through various digital technology and tools, e.g., Zoom, Teams, Flinga and Moodle.

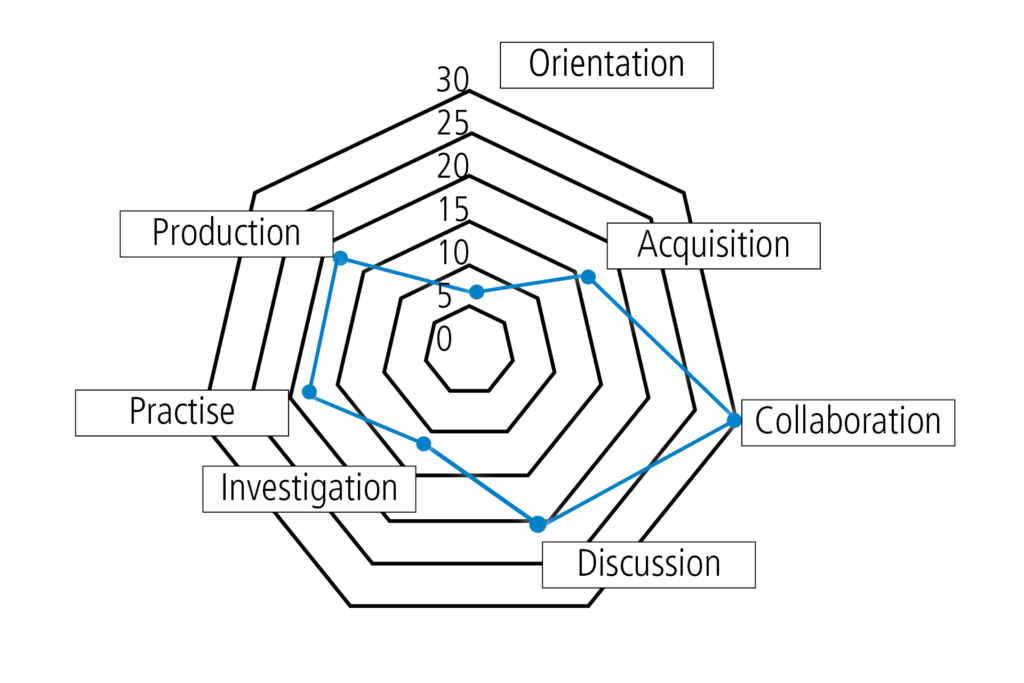

In the learning type activity graph below (Figure 2) the distribution of types of learning during the 5-day sprint week (40 hours) is visualised. It demonstrates that in the remote sprint collaboration through various digital platforms plays a decisive role in learning. The sprint encourages participant engagement and dialogue. (In an ideal situation sessions include many activities; thus, the number of hours comes to more than 40.)

- Orientation: introduction, icebreakers ect. 8

- Acquisition: read, listen, watch 16

- Collaboration: designing together 30

- Discussion: test, interviews, feedback 20

- Investigation: online search, benchmark 10

- Practise: feedback, iterate, improve 18

- Production: sketching, prototyping 19

Figure 2. ABC Learning Types in Haaga-Helia Porvoo Remote Design Sprint (Based on Laurillard, 2012)

As the remote sprint has many elements of all types of learning, it can be seen as a successful method for online and blended learning. It encourages collaboration, participant engagement and dialogue – all of them important 21st century skills. When developing the remote sprint further, the ABC model could be studied even more closely.

3. Method

The study is based on a case approach where the student feedback from the previous five face-to-face Design Sprints is compared to the feedback received from the first remote sprint. Similarities and differences are studied. Also, personal observations collected from sprint supervisors through interviews are analysed. The results are presented and discussed below.

Qualitative case study is a research method that makes it possible to explore a phenomenon with various data sources and to gain deep insight into the real-life phenomenon under study (Rashid et al 2019; Yin 2009). The case study approach was chosen, because it allows looking at the phenomenon from multiple viewpoints, gaining a holistic view and allowing the involvement of the researcher – both authors are deeply interested in developing the implementation of the method.

Most of the data collection for the case is based on written student feedback from all the Design Sprints. The empirical data is easily accessible, as it is stored in the course platforms in Moodle, and the questions have remained the same. A small part of the data analysed for this case consists of written (Konttinen & Moilanen, 2020) and oral testimonies of the remote sprint supervisors. Three supervisors were interviewed, the interviews were recorded and transcribed. The questions were about what was best about the sprint, what challenges the remote sprint presented and what needed special attention. The supervisors have taken part in several sprints so they can also see the differences between the previous sprints and the remote sprint.

There were 130 students in 18 teams, with 7 supervisors in the remote sprint in October 2020. Thus, each supervisor coached 2-3 teams. There were two commissions from the industry. Altogether 128 out of 130 students gave feedback at the end of the course together with peer and self-assessment through electronic Google Forms. Feedback has been collected with the same questions throughout the history of the Design Sprint. Previously, 534 students between spring 2018 and spring 2020 have answered the same questions. The questions focus on learning and student ideas for improvement. The answers to the questions have previously confirmed the supervisor observations that the students learn 21st century skills, e.g., collaboration, communication and creativity, through the sprint.

The questions were as follows:

- What did you learn during the process? Name at least three things related to, e.g., contents, methods, cooperation, time management etc.

- What was good about the Design Sprint?

- How could we develop the Design Sprint? Please, give some concrete suggestions.

The feedback given together with self-assessment might affect the results. However, the factors that came up were similar to the ones mentioned in the anonymous feedback given through Haaga-Helia official channels where after each module the students evaluate their learning experience and are encouraged to mention what promoted their learning.

The feedback after each implementation has been taken into consideration and for example, the length of the sprint was once shortened from 5 days to 4 days. However, the fifth day was reintroduced again for the remote sprint for students to familiarise themselves with the commissioner thoroughly before starting the process and to learn the tools they need to use. In addition, the assessment criteria have been the target of continuous development throughout the process – how to make assessment transparent and equal.

Because the feedback from each sprint has been taken into consideration when developing the next implementation, the feedback of the remote sprint of autumn 2020 (128 students working on 2 commissions) and the latest face-to-face implementation of spring 2020 (69 students working on 2 commissions) are compared more closely.

4. Results and discussion

In the following, the results of the student feedback given through Google Forms are presented. The student feedback is discussed in three main categories based on the feedback questions. Then the supervisor observations during the sprint and interview results are introduced.

4.1 Skills and competences – What did you learn?

When the students were asked what they learnt, many similarities between face-to-face and remote implementations came up. The students on both implementations mentioned learning new skills through the steps of the sprint process itself: creating new ideas, sketching solutions, prototyping and testing them, interviewing customers.

In addition, time management, English communication skills, working in groups with people they had not met before, and cooperation came up. Many also mentioned giving presentations and working under pressure as skills they learnt.

However, the skills that most students learnt in the remote sprint were teamwork online, using online tools and platforms (Flinga, Canva), in addition to creating websites and mock-ups. Those skills – apart from teamwork in general – were not mentioned in the feedback by the students in face-to-face implementations. Naturally, the remote sprint commissions were related more to the digital environment than before: virtual solutions, website, social media marketing, product development. That is why the prototypes and solutions were also more digital, for example websites (Weebly), tools for online events and social media.

“Learning a process which is really effective and useful for the future working life (a process which is actually used in many real life companies). Ideation and creativity were also a good part of it. Constant feedback was important to have to be able to develop the prototype”

4.2 Benefits of Design Sprint – What was good?

When asked what was good about the Design Sprint, factors such as working in mixed groups with students from other degree programmes, getting to know new people, working for real commissioners, supporting teachers came up. Therefore, the benefits of the remote sprint were similar to those brought up in the feedback of face-to-face implementations.

Before the remote sprint, supervisors feared that it would not be possible to create a great group spirit and make students network with one another due to the online environment. That is why it was relieving to realise that the factor that came up most often in the feedback, 40 students out of 128 mentioning it, was that support from the team, great atmosphere and getting to know new people promoted their learning and made the process enjoyable.

”Working with new people and getting new ideas from them.”

However, the students in face-to-face implementation mentioned creative, inspirational methods, for example Marshmallow challenge, painting/sketching during the sprint week. Those activities were easier to carry out in class than online and that is why they were replaced by other icebreakers, e.g., polls and chats, more suitable for an online environment – an aspect that will be paid more attention to in the next online implementation. Despite that the students in the remote sprint also mentioned the creative learning methods, such as the Design Sprint method itself, which made them think outside the box and leave their comfort zones: “The inner creativity awakening”. The pre-assignment facilitated understanding of the concept. The students also mentioned that industry cooperation and having “a real customer” was motivating.

In both implementations the support from the supervisors was mentioned, however, it came up more in the feedback of online implementations: the supervisors were easier to reach. The students just needed to ask for help in Zoom breakout room, and somebody was there to support. In face-to-face situations reaching the teacher can sometimes be more difficult, they might be in a different location or seem busy with some other tasks.

“I think that it worked quite well remotely! At first, I thought it’s going to be very hard, but we got many tips and tools on how to use various virtual tools to manage it. I also think that we received quite a lot support from the teachers and it was great to know that the commissioners were very excited to learn about our process and ideas!”

4.3 Future Design Sprints – What to develop?

When asked what the students would like to develop in the Desing Sprint, instructions came up: 23/128 wanted to have clearer instructions or said that supervisors were giving different instructions. However, in face-to-face implementation the corresponding amount was one fourth. In conclusion, giving the instructions at the same time for everybody, all students and supervisors listening, seemed to be effective. Furthermore, a wish for clearer instructions is a typical comment for any inquiry learning assignment.

The sprint process is always very intense and now 17/128 said that some days were exhausting and wished for shorter days or fewer tasks. However, the actual number of students mentioning that they would rather do it face-to-face was just 10/128. The intense nature of the sprint comes up often during the week also in face-to-face implementation.

Perhaps the biggest difference compared to face-to-face implementation was related to finding customer understanding on the second day of the sprint. Students found it difficult to find people to interview during a relatively short time (12/128). This challenge came up during the sessions, too. Usually, students go out and find informants outside campus. Now, due to COVID-19, they were hesitant to approach people without prior notice, for ad hoc interviews. In face-to-face implementations there was no mention of the difficulty of finding informants, although the hesitation about going outside the campus during the classes was noticeable. In the next remote implementation, more help will be provided, and students will be informed earlier that they need to conduct preliminary interviews and seek customer insight the next day.

Although the benefit of using the English language comes up regularly in the feedback, some students found using English and collaboration challenging – some were silent, did not co-operate or did not have their cameras on. In Zoom it is easier for passive/introverted people to stay silent than in the class, it is harder to engage them than in face-to-face implementation. Students were required to have the latest version of Zoom, use their name and photo in their profile and recommended to turn their cameras on. In the future, facilitators could emphasise the importance of keeping the cameras are on at least during the breakout room sessions, and perhaps take that into consideration even when assessing the sprint.

4.4 Supervisor experiences

Two supervisors of the remote sprint, the authors, already shared their initial experiences right after the sprint in their blog post (Konttinen & Moilanen, 2020). The first thoughts right after the sprint had to do with how well the method is suited for learning the 21st century skills as well as enthusiasm about the digital tools involved to make the sprint such a smooth experience online. One supervisor interviewed said that the sprint is like “coming from chaos to clarity”, when witnessing students develop viable concepts from initial uncertainty.

When planning a remote sprint, it is essential to create a trusting atmosphere and sense of community to foster collaboration, e.g., through icebreakers. Supervisors offer support in the main sessions and visit their assigned teams at all stages in breakout rooms. The sprint requires that students and supervisors devote the entire sprint week to the process. That way everybody is aware of the stages, instructions and progress. Peer support from other supervisors is very important: one supervisor oversees giving certain instructions and the others help by monitoring the chat, dividing the students into breakout rooms etc.

It is important that the supervisors pay special attention to the etiquette in the breakout rooms, remind the students to have cameras on and help students in case of communication problems. Similarly, they need to offer enough possibilities for breaks and remind students to go outside and eat snacks. These issues were also mentioned in the remote sprint guidelines developed by GV (Knapp et al., 2020) and by other people who have conducted design sprints online (Btesh et al., 2020; Ganesh & Garcia, 2020). In addition, when planning the next remote sprint further studies on online pedagogics e.g., ABC model, alternative platforms and tools can be interesting and useful.

Prior to the remote sprint, the supervisors were rather unsure and uncertain about the online format. Supervisors were surprised that the remote sprint went so well, and the results were so good. Indeed, supervisors thought that the sprint assignments were of better quality and more focused than in the previous sprints – both the pre-assignments as well as the end results. Of course, there are always things that could have been done differently. There were comments by the students that supervisors could have mastered technology better. However, both students and supervisors became more confident in the use of digital tools during the sprint.

5. Conclusion

In the stressful pandemic times, it was such a relief for everyone that the sprint worked out well remotely. We can now safely say that sprints can be implemented online, even as an international project, also after COVID-19. Infact, remote sprints and online learning may become the new normal as there are likely to be more pandemics. Sharing the best practices and experiences is important when developing new curricula and online pedagogics.

The study contributed to the supervisor understanding of the benefits of the remote sprint and encouraged them to carry it out even after the pandemic. The student feedback for the first remote sprint was perhaps surprisingly similar to the feedback received for the previous face-to-face sprints. It has always been interesting to see how the students mention many of the 21st century skills among the things they learnt during the sprint. They also highlight teamwork, collaboration and creativity among the good things they learnt and experienced. Another surprising insight was the fact that the sprint went so well: technology played along smoothly, and it was possible to adapt the sprint process to the remote format rather painlessly. Furthermore, more focus had to be given to establish trust among students and to create a collaborative learning environment than during the previous sprints. The support from other sprint supervisors and clear guidelines were of immense importance.

Both students and supervisors took the online sprint journey together to solve business problems and learn 21st century skills along the way. All participants became more familiar with online tools and technologies, new ways for collaboration and communication. The remote sprint brought along even closer cooperation between technology and humans – stressing the importance of the soft skills of the 21st century, the ones that separate machines from people. It was a transformational experience that made the participants better equipped to enter the future world of work.

References

- ABC Learning Design. (2020). Toolkit 2020 Resources. https://abc-ld.org/download-abc/

- Btesh, N., Goyeneche, E., Halladay, C., & Wells, C. (2020). How going 100 % virtual gave us an edge. Sprint Stories. https://sprintstories.com/how-going-virtual-gave-us-an-edge-96e87c8c0530

- Canton, J. (2015). Future Smart: Managing the Game-Changing Trends That Will Transform Your World. Da Capo Press.

- Frey, C. B., & Osborne, M. (2013). The Future of Employment. https://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/downloads/academic/The_Future_of_Employment.pdf?link=mktw

- Ganesh, S., & Garcia, C. (2020). What We Love and What We Hate About Remote Design Sprints. Parallel. https://www.parallelhq.com/blog/love-hate-remote-design-sprints

- Grant, A. (2021). Think Again. WH Allen.

- Gudmunds, V. (2018). Reykjavik University: Design Sprints with over 460 students in 92 teams. Sprint Stories. https://sprintstories.com/reykjavik-university-design-sprints-with-over-460-students-in-92-teams-31c97f69437e

- GV. (2019). The Design Sprint. https://www.gv.com/sprint/

- Haaga-Helia. (2021). Haaga-Helia’s strategy. https://www.haaga-helia.fi/en/haaga-helias-strategy

- Hakkarainen, K., Lonka, K., & Lipponen, L. (2004). Tutkiva oppiminen – Järki, tunteet ja kulttuuri oppimisen sytyttäjinä. WSOY.

- Huijser, H., Kek, M. Y. C. A., & Terwijn, R. (2015). Enhancing Inquiry-Based Learning Environments with the Power of Problem-Based Learning to Teach 21st Century Learning and Skills. Inquiry-Based Learning for Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (Stem) Programs: A Conceptual and Practical Resource for Educators. Innovations in Higher Education Teaching and Learning, 4, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, (pp. 301–320). https://doi.org/10.1108/S2055-364120150000004017

- Iñiguez-Berrozpe, T., & Boeren, E. (2019). Twenty-first century skills for all: adults and problem solving in technology rich environments. Technology, Knowledge and Learning. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10758-019-09403-y

- Isacsson, A., Slotte, S., & Wikström-Grotell, C. (2020). Future work skills in higher education: Learning to be an international intrapreneur. In K. Mäki (ed.), Oppiva asiantuntija vai asiantuntijaksi opiskeleva? Korkeakouluopiskelijoiden työelämävalmiuksien kehittäminen. (pp. 52–63). Haaga-Helia. https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/411667/oppiva-asiantuntija-web.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Knapp, J., Zeratsky, J., & Kowitz, B. (2016). Sprint – How to solve big problems and test new ideas in just five days. Simon & Schuster Paperpacks.

- Knapp, J., Zeratsky, J., & Colburn, J. (2020). The Remote Design Sprint Guide. https://www.thesprintbook.com/remote

- Konttinen, A., & Moilanen, N. (2015). Inquiry learning in practice – information sharing among first semester tourism students and supervisors. In: R. Sandelin (Ed.), Esseitä Porvoo Campukselta. (pp. 5–23). Haaga-Helian julkaisuja. Kehittämisraportit ja tutkimukset 2015, Haaga-Helia ammattikorkeakoulu. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978- 952- 6 619 -51-4

- Konttinen, A., & Moilanen, N. (2019, toukokuu 2). Design Sprint – a method for the 21st century skills. eSignals. https://esignals.fi/en/category-en/design-sprint-a-method-for-the-21st-century-skills/#c1767d94

- Konttinen, A., & Moilanen, N. (2020, joulukuu 12). Ohjauksen uusi normaali – sprintti elinikäiseen oppimiseen. eSignals. https://esignals.fi/kategoria/pedagogiikka/ohjauksen-uusi-normaali-sprintti-elinikaiseen-oppimiseen/#c1767d94

- Konttinen, A., & Sivonen, A. (2018). It’s all about the students: the student-centered Campus 2.0 curriculum. In: R. Anckar (Ed), Yhdessä oppimassa: ratkaisuja oppimiseen ja ohjaamiseen Haaga-Helian Porvoo Campukselta (pp.78–91). Haaga-Helian julkaisut, Haaga-Helia ammattikorkeakoulu. URN:ISBN:978-952-7225-61-5

- Latorre-Cosculluela, C., Suárez, C., Quiroga, S., Sobradiel-Sierra, N., Lozano-Blasco, R., & Rodríguez-Martínez, A. (2021). Flipped Classroom model before and during COVID-19: using technology to develop 21st century skills. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, vol. ahead-of-print no. ahead-of-print. https://doi-org.ezproxy.haaga-helia.fi/10.1108/ITSE-08-2020-0137

- Laurillard, D. (2012). Teaching as a design science: Building pedagogical patterns for learning and technology. Routledge.

- Magistretti, S., Dell’Era, C., & Doppio, N. (2020). Design sprint for SMEs: an organizational taxonomy based on configuration theory. Management Decision, 58(9), 1803–1817. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-10-2019-1501

- McKinsey & Company. (2021). The Future of Work after Covid-19. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work

- OECD. (2018). Future of Education and Skills. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/contact/E2030_Position_Paper_(05.04.2018).pdf

- OECD. (2020). Continuous Learning in Working Life in Finland. http://www.oecd.org/publications/continuous-learning-in-working-life-in-finland-2ffcffe6-en.htm

- Pölönen, P. (2020). Tulevaisuuden identiteetit. Otava.

- Rashid, Y., Rashid, A., Warraich, M. A., Sabir, S. S., & Waseem, A. (2019). Case Study Method: A Step-by-Step Guide for Business Researchers. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919862424

- Ritalahti, J. (2015). Inquiry Learning in Tourism. Tourism Education: Global Issues and Trends. Tourism Social Science Series, 21, 135–151. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1571-504320150000021007

- Schmidt, E., & Cohen, J. (2014). The New Digital Age: Transforming Nations, Businesses, and Our Lives. Vintage Books.

- Silber, V. V., Eshet, A. Y., & Geri, N. (2019). Tracing research trends of 21st‐century learning skills. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(6), 3099–3118. https://bera-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bjet.12753

- Sprint Stories. (2019). Sprint Stories. https://sprintstories.com/

- Toda, A. M., Palomino, P. T., Oliveira, W., Rodrigues, L., Klock, A. C. T., Gasparini, I., Cristea, A. I., & Isotani, S. (2019). How to Gamify Learning Systems? An Experience Report Using the Design Sprint Method and a Taxonomy for Gamification Elements in Education. Educational Technology & Society, 22(3), 47–60.

- VARK Learn Limited. (2021). Introduction to VARK. Do you know how you learn? https://vark-learn.com/introduction-to-vark/

- WEF (World Economic Forum). (2020). The Future of Jobs Report 2020. https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-of-jobs-report-2020

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case Study Research – Design and Methods. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Yoo, H. (2021). Research-to-Resource: Use of Technology to Support 21st Century Skills in a Performing Ensemble Program. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 39(2), 10–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/8755123320953435

- Young, C., & Perovic, N. (2020). ABC LD – A new toolkit for rapid learning design. https://cpb-eu-w2.wpmucdn.com/blogs.ucl.ac.uk/dist/3/513/files/2020/07/EDEN-2020-ABC-LD-Toolkit-CY-NP-final.pdf