Abstract

This study builds on the notion of viewing bricolage as a mindset of resourcefulness rather than seeing it only as a resource integration or resource scarcity. Particularly, we study service innovation processes to shed light on how entrepreneurs use stories of their experience and interactions as a vehicle for mediating means into resources. In order to understand how particular stories contribute to service innovation processes we adopt a process-based methodology (Langley, 1999; Van de Ven & Huber, 1990). Our study shows how a certain knowledge base and a worldview enabled the entrepreneur to understand the power of his own experiences, turn them into opportunities and utilise them as a source for stories of entrepreneurial outcomes. These stories then in turn mediated the available means into resources in various ways.

Keywords: Bricolage, resourcefulness, entrepreneurial stories

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship research has increasingly shifted towards studying how entrepreneurs identify and manage opportunities, and the role of cognitive scripts in decisions making (Fayolle & Liñán, 2014; Read et al., 2016). Bricolage has gained interest in this field as it demonstrates how opportunities can be utilised and created even in scarce environments and it has been claimed to foster innovativeness. Rather than focusing on certain environmental conditions, this study builds upon Halme et al. (2012), who suggest that bricolage is a mindset of resourcefulness which leads to addressing opportunities and challenges in a certain way.

In this paper, we conceive resourcefulness as a relational concept which can be studied as a process consisting of events unfolding over time rather than understanding resourcefulness as a measurable condition (MacKinnon & Derickson, 2013). Our study contributes to the knowledge of bricolage by showing how resourcefulness as a mindset enables transforming means (who you are, who you know and what you know) into resources (e.g. human and financial resources) and how stories serve as vehicles in this mediation process.

2. Bricolage

Entrepreneurial bricolage concerns organising new combinations of whatever resources are at hand to address an opportunity that has been discerned (Di Domenico et al., 2010). The concept of bricolage in entrepreneurship literature builds upon Lévi-Strauss (1967), who identified bricolage behaviours and described them as making do with whatever is at hand in contrast to the engineering model of gathering needed resources for an intended design.

Originally, the verb ‘bricoleur’ was used in French to describe a ball rebounding or to hunting, shooting or riding to describe a movement deviating from the direct course. Later, Lévi-Strauss used the word bricoleur to describe ‘someone who works with his hands and uses devious means compared to those of a craftsman’ and ‘expresses itself by means of a heterogeneous repertoire which, even if extensive, is nevertheless limited…, because it has nothing else at its disposal’ (Lévi-Strauss, 1967, p. 11). In this definition, the set of resources is closed and therefore the bricoleur has to make do with whatever is at hand, regardless of the project, and the resources are acquired without any particular project in mind ‘on the principle that they may always come in handy’ (Lévi-Strauss, 1967, p. 11). Thus, the bricoleur starts the process in a retrospective manner, viewing the set of resources and considering how the set at hand may enable to solve the problem. The possibilities of recombining the resources is limited by the history of each element and its predetermined features, which already possess a sense. Conversely, there are many recombination options and changing one element may change the effect significantly, the effect being difficult to imagine beforehand (Lévi-Strauss, 1967).

In constraint theories (e.g. Casson, 1982) scarcity was seen as an obstacle, wherein resources were as given, and were objective, unproblematic and not dependent of the specific organisation (Baker & Nelson, 2005). Contrastingly, the bricolage perspective considers that scarcity can be a source for triggering opportunity creation (Salunke et al., 2013). Bricoleurs address the limitations set by the scarce environment by actively looking for solutions using the resources at hand and acting instead of thinking that nothing can be done due to scarce resources (Baker & Nelson, 2005). Resources at hand can be defined as free or cheap (Baker & Nelson, 2005) as well as not new (Duymedjian & Rüling, 2010). Bricoleurs discover opportunities while enacting resources instead of viewing opportunities as objective and external, they consider new value for forgotten, discarded, worn or single-use items, engage customers, suppliers and hangers-on in the project, create services by amateur or self-taught skills, create markets by offering otherwise unavailable services as well as refuse to consider standards and regulations as limitations (Baker & Nelson, 2005). In which case adopting a bricolage approach, may enable a company to survive in a competitive environment by exploiting new opportunities through inexpensive means, and deploying resources at hand, instead of using exactly the right types and levels of resources (Baker & Nelson, 2005).

However, scarcity is a complex concept (Witell et al., 2017). Resource scarcity may be concerned with tangible resources like equipment, finance, land, institutions and infrastructure (Barrett et al., 2015; Cunha et al., 2014); or intangible resources like knowledge, skills, ideas, time and network (Baker & Nelson, 2005). Resource scarcity may be internal e.g. employee capabilities (Gupta et al., 2016) or external e.g. customer’s lack of financial or competence resources to design and test the service (Cunha et al., 2014; Heinonen et al., 2013) or potential partner organisations may not have resources to partner in developing services (Barrett et al., 2015; Srinivas & Sutz, 2008).

It has been argued that a resource scarce environment may lead to more creative solutions (Moreau & Dahl, 2005; Mullainathan & Shafir, 2009), and therefore companies may even create scarce resource environments intentionally (Baker & Nelson, 2005). A consequence of using only resources at hand through the bricolage approach, has also been said to reduce revenues, and to lead organisations not to focus on new, demanding, customers (Senyard et al., 2009); although it will cause delays in the innovation process and reduce service quality (Witell et al., 2017).

Research on bricolage has often focused on behaviors, thus emphasising the action of resource integration. When studying processes and cognitive scripts, the importance of understanding bricolage as a mindset starts to emerge. Thus, enacting bricolage when encountering challenges and opportunities requires a certain knowledge base and worldview (Halme et al., 2012). The mindset of a bricoleur is not to try to avoid challenges, but to solve them and to come up with new ideas to overcome the obstacles. In a similar way, the bricoleur identifies and creates opportunities by actively reflecting upon one’s own experiences and interaction with one’s network (Lassila, 2020).

In behavioral psychology resourcefulness has been studied in the context of stressful life events to identify means that enable coping in these events (Rosenbaum, 1989).

Entrepreneurial resourcefulness can be seen not only as means to cope with challenges (Powell & Baker, 2011), but also as an ability to identify opportunities and to act upon them (Misra & Kumar, 2000). In this study we consider that opportunities are not only identified but also created thus viewing entrepreneurial resourcefulness particularly as means to identify and create opportunities.

3. Methodology and methods

In order to understand how resourcefulness is used in service innovation we adopt a process- based methodology (Van de Ven & Huber, 1990). Thus, entrepreneurship is seen as a journey (McMullen & Dimov, 2013) while innovative ideas are understood to emerge iteratively in interaction with the external environment (Dimov, 2007). Process research studies how events unfold over time by systematically mapping changes in the invention and implementation of new ideas, focusing on the people who develop and carry out them, transactions with other stakeholders, the context in which the developments take place, and the outcomes (Van de Ven & Rogers, 1988).

As a part of a broader research project, we have employed a range of methods between 2013 to 2017, including ethnographic observation, interviews and document analysis. When starting the analysis process, the first codification was done with the Nvivo program. The analysis aimed to identify events and study the chain of events (Van de Ven & Huber, 1990). We continued the research process by arranging the events in temporal order, drawing on visual maps, identifying meaningful events from the qualitative incident data, arranging events in temporal brackets, and developing a narrative (Langley, 1999; Langley et al., 2013). We identified a final set of 337 events and listed these events in temporal order in Excel. In process research “it is important to note that the sample size for a process study is not the number of cases, but the number of temporal observations” (Langley et al., 2013, p. 7).

We used a narrative to tell a rich contextual story of Heltti, which is our research site, describing how events unfolded (Langley et al., 2013). Narratives shed light on insights about organisations, by enabling better explanations through being close to the phenomena under study (Pentland, 1999).

4. Background to the research site

Our research site is a new venture, Heltti, which was established by a married couple, Jack and Laura (pseudonym as all the other names and company names here after), in 2014 in Finland. Heltti offers occupational health care (OHC) services, which aim at improvements and uplifting changes among employees, organisations and the ecosystem (Anderson et al., 2013). We selected Heltti because of the expansive site access it afforded us due to its open organisational culture, as well as the potential to research how it developed its new services. Heltti is an interesting research site as it aims at decreasing health care costs by shifting the focus from the traditional reactive and disease-treatment-oriented occupational health care to enhancing preventive health care and well-being. The company offers occupational healthcare and wellbeing services to knowledge workers by deploying the business model as advocated by (Den Ouden, 2011) which describes the offering as being a meaningful and transformational innovation, which addresses the different levels of stakeholder value. The service which aims at changing behaviour, disrupts the traditional structures in the ecosystem, and requires a longer time period for value creation to be realised; and quite importantly, as a radical solution, it is not yet evident if the business model is a viable one that is accepted by the customers. However, Heltti aims to challenge the traditional design of the service for occupational health care practices by focusing on the design and provision of preventive services, offering for a fixed monthly fee, and by handling approximately 70% of their services digitally through eHealth solutions which is in contrast to the traditional face-to-face service delivery methods. Digital services have entered in health care globally with an aim to enhance the quality and safety of health care by storing, and transmission of data, supporting clinical decisions and facilitating care from a distance (Black et al., 2011).

Our investigation covers four years, from the time when Heltti as a company did not exist (2013) to a time when their turnover exceeded one million euros (Jan 2017). Since then Heltti has continued to grow while reaching over 5 million euro turnover in 2019. Financial Times listed Heltti in place 276 among the 1000 European fastest growing companies 2020.

All interviewees signed a participant consent form, which indicates that they participate in the research voluntarily and that they have a right to withdraw from the research. All data was made anonymous, and only the role or title is mentioned. Individual identities are kept confidential unless we were provided explicit consent to do otherwise. A separate agreement has been signed with Heltti to allow us to observe their meetings and use their documents as research material. It has been agreed that Heltti Oy as a case company can be mentioned in all research publications and presentations.

5. Findings

Stories played a critical role in service innovation processes in Heltti. Thus, describing how Jack, the founder and CEO of Heltti, utilised stories as a vehicle to transform means into resources, sheds light to understanding the role of resourcefulness in service innovation processes.

Earlier studies suggest that stories are used to share values, exchange knowledge (Whittle et al., 2009), develop trust, motivate people (O’Gorman & Gillespie, 2010) as well to construct organisational legitimacy (Golant & Sillince, 2007). All these aforementioned purposes can be identified among the stories of Heltti. Particularly during the early days of the new venture, Jack used stories as organisational symbols, to legitimate the new venture (Lounsbury & Glynn, 2001) by communicating socially constructed meanings, which has been found to help with acquiring resources (Zott & Huy, 2007). These stories Jack told seemed to help in confronting legitimation issues that the company encountered as a new venture with disruptive intention (Low & Abrahamson, 1997), thus enabling access to different resources (Lounsbury & Glynn, 2001). Jack started to construct stories that legitimised their means and aspirational goals by coherently addressing ‘questions about who they are, why they are qualified, what they want to do and why they think they will succeed’, which has been found to be beneficial when a service emerges through complicated, nonlinear processes (Lounsbury & Glynn, 2001, p. 550). In following we analyse four separate extracts from the data collected during the fieldwork time that construct three different stories about the innovation process.

5.1 Story 1: Drinking wine

Jack was a co-founder of a Finnish law firm before establishing Heltti. This first story explains who Jack is and why a respected lawyer moved to the occupational health care industry. By telling this situated story, Jack explains his beliefs about his motives and who he is, thus developing and maintaining his life story and self-concept (McLean et al., 2007). Besides, as Jack himself has no professional experience in the occupational health care sector, by talking about his relatives working in the health care sector, he aims to gain legitimation for his choice.

It was in the Independence Day 2012 at a skiing cottage when the rest of the family was already sleeping, and I had a couple of glasses of red wine, I got this big eureka moment. Damn, it has been in front of me all the time. What can you do if your grandparents are doctors, parents are doctors, brother is a doctor, cousin is a doctor, uncle is a doctor, cousin is a doctor and you are the black sheep in the family? And even your own wife is working in the health care sector. (…) Suddenly it glinted that, damn, this is the next thing, it is a healthcare company and it is particularly in occupational health care. I had a very concrete image of it all, and the best thing was that it sounded like a good idea even in the next morning. (Jack, founder)

This fact that Jack is a lawyer who aims to disrupt the OHC market was also exploited in articles written about Heltti. The Finnish Entrepreneurship Federation published one of the first media exposures of Heltti with the following title:

A lawyer intends to shake occupational health care: Jack, The owner of the Law Firm X and board member of the Boardman, network aims to disrupt occupational health care (Finnish Entrepreneurship Federation, 7.4.2014)

5.2 Story 2: Chinese village doctor

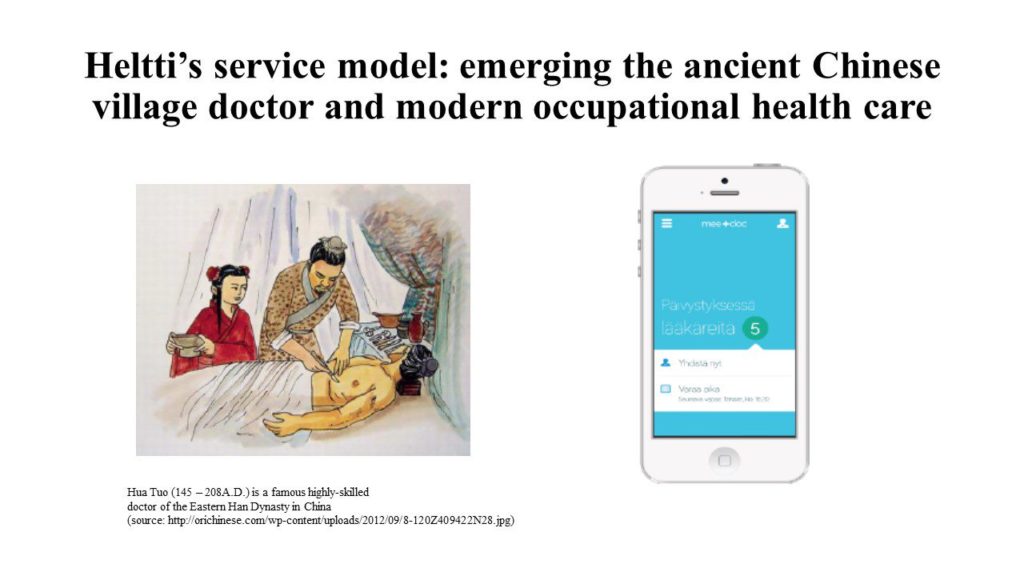

Serendipity plays a role in the second story, which emerged through perceiving opportunities in a story that Jack heard. The story is about a Chinese village doctor, which resonated well with Heltti’s value proposition: keeping people healthy. A person in Jack’s network told the story of a Chinese village doctor triggered by the idea of predictive health care services.

Encountering this story enabled Jack to combine the ideas of fixed pricing and enhancing wellbeing to demonstrate the value and relevance of their new service (Lounsbury & Glynn, 2001). Through this ancient story, the unfamiliar, new approach was turned into something easy to understand and was legitimated by framing the new service through a metaphor (Salancik & Leblebici, 1988). Fixed pricing had raised suspicions about the service quality among the potential customers, whereas the Chinese Doctor story changed the fixed pricing to be an incentive for keeping people healthy.

Another thing is that instead of making NDAs of everything and being quiet, we should talk much with different kinds of people. I talked about our idea with one person, and I told them that we had proceeded and we had discussed about a fixed pricing model. He stated that Jack, it is, like, have you ever heard about the story of the Chinese doctor? People in the village paid for the doctor, but by no means did they pay based on the number of clinical visits and operations. Instead, all the healthy villagers paid. Based on that principal, the better the villagers felt, the better the doctor earned. He had financial incentives to keep the villagers healthy.

When I started to think about this, I wondered that, where did we lose this business model? Now, we have financial incentive to keep the people sick in our classical model. This opened my eyes to understand that we shall turn this upside down and enter the market with a fixed pricing model. And we were already prepared, that this kind of pricing model requires us to create services for healthy people. But what we were not prepared for, and this is something we learnt only after starting our business, was that it is not only a pricing model, but it is a whole business model. It turns upside down most of the things we are doing, how we do it and where we aim at in our business, what we measure, what is good and what is bad. (Jack, founder)

When presenting Heltti’s business model, the Chinese village doctor story was often combined with a picture of a mobile phone (Figure 1). This served as a contrast, but in particular it highlighted that Heltti’s business model was a modern version of the ancient Chinese village doctor concept.

5.3 Story 3: The white coat story

The third story illuminates how Heltti’s service experience differed from the traditional OHC services. The white coat story was based on Jack’s own vision of what the service experience in Heltti would be, thus serving as a critical intangible resource.

We wanted to rethink what happens when you come to the health care clinic, even though we don’t use that term (health clinic). If we think about the classic image, when you come here and ring the bell, then the buzzer starts ringing, and you open the door and you go and enrol yourself in the reception, you inform who you are and who you are going to meet (…) Then he calls you, ‘Lassila’.

Then you go to the room and it is furnished so that there is a big table, and the doctor has a big good chair with a high backrest. (…) The whole situation is designed so that the doctor has all the signs of authority and the other one, be it, e.g., a lawyer in this example, so he is put in every respect in a submissive position. (…) What we wanted to do is that practically when you ring the bell, the person who has an appointment with you comes to open the door. So we turn the waiting the other way around so that the doctor waits and not the member who has come to wait for you. (Jack, founder)

When ideating what Heltti’s service could be, one of the most important aims for Jack was to create a non-hierarchical organisation in health care, thus changing what he understood to be the dominant culture in OHC in Finland. The story about the doctor being the person in control and above the patient, while the patient is in the role of an object, reveals the

underlying assumptions of power in the health care service setting. The doctor’s white coat symbolises medical authority and respect (Hochberg, 2007). Jack’s story of the white coat reveals how the hierarchical culture is embedded in OHC practices in different ways such as interior design, processes and cultural practices. A story, as an intangible resource, revealed the emotion and feelings that the service creates, which is otherwise difficult. Later, this story also served as a script for videos that demonstrated Heltti’s customer journey.

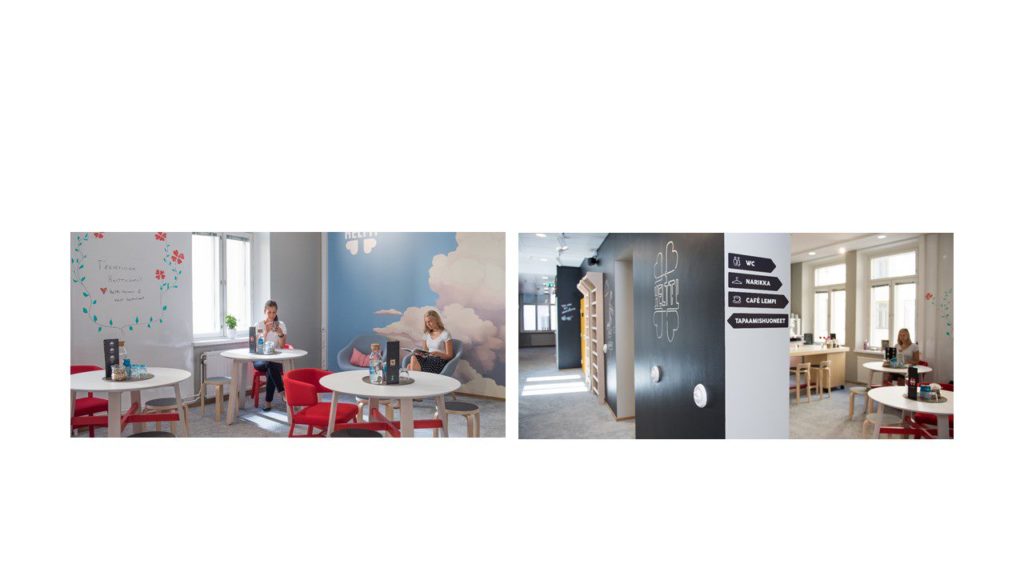

The white coat story was a vehicle to communicate Heltti’s intended service experience for different stakeholders (Lounsbury & Glynn, 2001). The service experience that Jack wanted to create was also embedded in interior design and the layout of the premises. The ‘look and feel’ of Heltti became an important element of Heltti’s service experience and one of the concrete artefacts of disruption.

Copyright with permission.

Even though Heltti’s premises were carefully designed, scarcity and handyman solutions, which are associated with bricolage (Lévi-Strauss, 1967), became especially apparent in its original premises. When making decisions about the location, Jack considered the rental agreement to be a major risk for a new company while trying to find an affordable location. He rationalised the choice of the location within a sports centre by being close to other services also aimed at enhancing health. However, the location was far from the city centre and was not easily accessible. The clinic itself was situated on the cellar level at the end of a long corridor, and the visitors needed to pass people in their sports outfits putting their bags in lockers. It also became rather apparent for the customers that the interior design solutions were based on affordability. The closed front door, someone personally coming to open the door, the unconventional interior design and the cheerful welcome were all rather surprising elements for a health clinic. The whole health clinic, with its ‘look and feel’, combined with the unconventional customer journey, seemed rather experimental. By highlighting the contradiction between the traditional customer journey and Heltti’s customer journey, the founders aimed at appealing to an emotional level.

Finally, in May 2017, Heltti was able to move to a central location and to fulfil the premises set in white coat story more fully. When entering the new premises, customers were encouraged to change into slippers to create a homely feeling. The waiting room was designed like a café (Figure 3), where the customer could work and enjoy a cup of coffee whilst waiting for the appointment. The appointment rooms followed the same design as in the earlier Heltti premises with round tables and red chairs.

5.4 Story 4: Disruption

“We are changing the way people think about visiting a doctor, the disruption is similar to what has happened in banking’, describes Jack, CEO and co-founder of Heltti. ‘Going to the doctors can mean picking up your smartphone and using a digital connection (…) We believe health care shouldn’t aim for as many patient visits as possible, but for finding the most effective ways to treat people and prevent illnesses”, he says. (Finnfacts 18.1.2017)

One of the core elements of Heltti’s service was that it would be efficient by being close to the customer. This was something that Laura in particular actively advanced, as she had found the traditional service delivery as inefficient. The first idea was to achieve closeness via a Heltti car which would take the doctors and nurses to see end-users, wherever they were.

This was soon found to be too expensive and inefficient. Through interacting with digital service companies and studying future trends in the healthcare industry, the solution was found in digital services. Together with a partner company, the founders started cocreating the HelttiMe service, which would help the user follow their own health data and give access to new kind of caring processes, e.g., through video connection. HelttiMe was planned to include both social and gaming elements. However, before these ideas were implemented, a new opportunity emerged. By coincidence, Laura found another service provider that could provide a chat service that allowed the patient to communicate with the health care personnel in a protected environment. The service was tested through a pilot project, and later, HelttiMe chat evolved to be the most common channel to make contact with Heltti. Exploiting this contingency appeared to be one of the key solutions in Heltti’s early history.

When the founders realised that HelttiMe chat was one of the cornerstones of their service, they started actively communicating that 70% of health issues are handled remotely with Heltti, thus aiming at positive reinforcement to use the digital channels and symbolising the modern nature of Heltti’s services.

6. Conclusions

This study shows how a certain knowledge base and worldview made the entrepreneur understand the power of his own experiences, turn them into opportunities and utilise them as a source for stories. These stories then in turn mediated the available means into resources in various ways.

The founders of Heltti aimed to change the Finnish OHC sector by introducing a fixed pricing model, focusing on preventive healthcare services, offering digital services and creating a non-hierarchical work culture. In the beginning Heltti experienced difficulties in attracting customers and employees as the new venture was not yet approved in people’s minds. Stories enabled communicating these changes in very concrete terms to different stakeholders. Consequently, stories served as vehicles that enabled mediating available means into resources in terms of both human resources and financial resources. The prerequisite was the mindset of resourcefulness of the two founders, when encountering opportunities and obstacles during the entrepreneurial journey.

This study contributes to understanding the bricolage as a mindset of resourcefulness and the role that stories play in this process. Furthermore, from the viewpoint of resourcefulness, bricolage as a mindset may provide potential in service innovation processes, not only for entrepreneurs but for managers and service developers in general.

References

- Anderson, L., Ostrom, A., Corus, C., Fisk, R., Gallan, A., Giraldo, M., . . . Rosenbaum, M. (2013). Transformative service research: An agenda for the future. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 1203–1210.

- Baker, T., & Nelson, R. (2005). Creating something from nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3), 329–366.

- Barrett, M., Davidson, E., Prabhu, J., & Vargo, S. L. (2015). Service innovation in the digital age: Key contributions and future directions. MIS Quarterly, 39(1), 135–154.

- Black, A. D., Car, J., Pagliari, C., Anandan, C., Cresswell, K., Bokun, T., et al. (2011). The impact of eHealth on the quality and safety of health care: A systematic overview. PLoS Medicine, 8(1), e1000387.

- Casson, M. (1982). The entrepreneur: An economic theory. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Cunha, R., Oliveira, P., Rosado, P., & Habib, N. (2014). Product innovation in Resource‐Poor environments: Three research streams. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 31(2), 202–210.

- Den Ouden, E. (2011). Innovation design: Creating value for people, organizations and society. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Di Domenico, M., Haugh, H., & Tracey, P. (2010). Social bricolage: Theorizing social value creation in social enterprises. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(4), 681–703.

- Dimov, D. (2007). Beyond the single-person, single-insight attribution in understanding entrepreneurial opportunities. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(5), 713–731.

- Fachin, F. F., & Langley, A. (2017). Researching organizational concepts processually: The case of identity. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management. Research Methods. SAGE, 308–327.

- Fayolle, A., & Liñán, F. (2014). The future of research on entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 663–666.

- Golant, B. D., & Sillince, J. A. (2007). The constitution of organizational legitimacy: A narrative perspective. Organization studies, 28(8), 1149–1167.

- Gupta, V., Chiles, T., & McMullen, J. (2016). A process perspective on evaluating and conducting effectual entrepreneurship research. Academy of Management Review, 41(3), 540–544.

- Halme, M., Lindeman, S., & Linna, P. (2012). Innovation for inclusive business: Intrapreneurial bricolage in multinational corporations. Journal of Management Studies, 49(4), 743–784.

- Heinonen, M., Holmlund, T., Gebauer, H., & Reynoso, J. (2013). An agenda for service research at the base of the pyramid. Journal of Service Management, 24(5), 482-502.

- Hochberg, M. S. (2007). The doctor’s white Coat: An historical perspective. AMA Journal of Ethics, 9(4), 310–314.

- Klag, M., & Langley, A. (2013). Approaching the conceptual leap in qualitative research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(2), 149–166.

- Langley, A. (1999). Strategies for theorizing from process data. Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 691–710.

- Langley, A., Smallman, C., Tsoukas, H., & Van de Ven, A. H. (2013). Process studies of change in organization and management: Unveiling temporality, activity, and flow. Academy of management journal, 56(1), 1–13.

- Lassila, S. (2020). The role of causation, effectuation and bricolage in new service development processes (Doctoral dissertation, University of Westminster).

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1967). The savage mind. University of Chicago Press.

- Lounsbury, M., & Glynn, M. A. (2001). Cultural entrepreneurship: Stories, legitimacy, and the acquisition of resources. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6–7), 545–564.

- Low, M. B., & Abrahamson, E. (1997). Movements, bandwagons, and clones: Industry evolution and the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(6), 435–457

- MacKinnon, D., & Derickson, K. D. (2013). From resilience to resourcefulness: A critique of resilience policy and activism. Progress in Human Geography, 37(2), 253–270.

- McLean, K. C., Pasupathi, M., & Pals, J. L. (2007). Selves creating stories creating selves: A process model of self-development. Personality and social psychology review, 11(3), 262–278.

- McMullen, J. S., & Dimov, D. (2013). Time and the entrepreneurial journey: The problems and promise of studying entrepreneurship as a process. Journal of Management Studies, 50(8), 1481–1512.

- Misra, S., & Kumar, E. S. (2000). Resourcefulness: A proximal conceptualisation of entrepreneurial behaviour. The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 9(2), 135–154.

- Moreau, C. P., & Dahl, D. W. (2005). Designing the solution: The impact of constraints on consumers’ creativity. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(1), 13–22.

- Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2009). Savings policy and decision-making in low-income households. Insufficient Funds: Savings, Assets, Credit, and Banking among Low-Income Households, 121, 140–142.

- O’Gorman, K. D., & Gillespie, C. (2010). The mythological power of hospitality leaders? A hermeneutical investigation of their reliance on storytelling. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 22(5), 659–680.

- Pentland, B. T. (1999). Building process theory with narrative: From description to explanation. Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 711–724.

- Powell, E. E., & Baker, T. (2011). Beyond making do: Toward a theory of entrepreneurial resourcefulness. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 31(12), 2.

- Read, S., Sarasvathy, S. D., Dew, N., & Wiltbank, R. (2016). Response to arend et al: Co- creating effectual entrepreneurship research. Academy of Management Review. Published Online before Print October, 30, 2015.

- Salancik, G. R., & Leblebici, H. (1988). Variety and form in organizing transactions: A generative grammar of organization. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 6(1–31), 330

- Salunke, S., Weerawardena, J., & McColl-Kennedy, J. R. (2013). Competing through service innovation: The role of bricolage and entrepreneurship in project-oriented firms. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 1085–1097.

- Senyard, J. M., Baker, T., & Davidsson, P. (2009). Entrepreneurial bricolage: Towards systematic empirical testing.

- Srinivas, S., & Sutz, J. (2008). Developing countries and innovation: Searching for a new analytical approach. Technology in Society, 30(2), 129–140.

- Van de Ven, A., & Huber, G. (1990). Longitudinal field research methods for studying processes of organizational change. Organization Science, 1(3), 213–219.

- Van de Ven, A., & Rogers, E. (1988). Innovations and organizations: Critical perspectives. Communication Research, 15(5), 632–651.

- Whittle, A., Mueller, F., & Mangan, A. (2009). Storytelling and character: Victims, villains and heroes in a case of technological change. Organization, 16(3), 425–442.

- Witell, L., Gebauer, H., Jaakkola, E., Hammedi, W., Patricio, L., & Perks, H. (2017). A bricolage perspective on service innovation. Journal of Business Research, 79, 290–298.

- Zott, C., & Huy, Q. N. (2007). How entrepreneurs use symbolic management to acquire resources. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 70–105.