The continuing societal and environmental inequalities, which cannot be adequately addressed by the capitalistically oriented market, have focused attention on organizations that combine enterprise with an embedded social purpose. Scholarly interest in social enterprise has advanced beyond the early focus on definition and context to examine the impact of hybridity on management and performance. By applying the resource-based theory, the authors identified the motivation of employees, the customer as well as the brand and/or reputation of social enterprises as possible sources of sustained competitive advantage. The authors propose future research to investigate whether the industry and the typology of the social enterprise influence the type of resources exploited to create sustainable competitive advantage.

1. Introduction

The growing economic disparities, persistent poverty and environmental change have resulted in the emergence of organizations that combine entrepreneurial activities with an embedded social, societal or environmental purpose. The defining characteristics of these organizations – often referred to as “Social Enterprises” (SE) – are their hybrid nature (Pache & Santos, 2013; Battilana & Dorado, 2010; Moizer & Tracey, 2010) as well as the pursuit of a dual mission to achieve financial sustainability and to address social imbalances (Doherty et al., 2014; Pache & Santos, 2013; Tracey et al., 2011). Within the management and organization literature, hybridity describes organizations that extend beyond institutional boundaries (Jay, 2013; Pache & Santos 2013). Social enterprises thus combine different institutional characteristics and therefore cannot be explicitly characterized as private, public or non-profit organizations (Maretich & Bolton, 2010; Ryder & Vogeley, 2017).

According to Battilana et al. (2015), the hybrid nature of SE´s always demands a prioritization of resources between economic necessities and social improvements. For this reason, resource allocation and exploitation are of central importance. In this context, we strive to identify the essential VRIO resources – resources that are, according to Barney (1990), valuable, rare, inimitable and organized to be exploited to create (sustained) competitive advantage – for social enterprises and how these resources are exploited to create (sustained) competitive advantage. This study is necessary to understand the current success of social enterprises and to relate it to purely economically operating companies.

Since social enterprises pursuit a dual mission – in particular, achieving financial sustainability, while creating social value – they need both, generate sustainable revenues to reinvest in commercial operations and maintain investments in social projects. Accordingly, social enterprises operate under conditions of resource scarcity, which may “threaten the long-term sustainability of the enterprise” (Moizer & Tracey, 2010, p. 252). However, the long-term success of social enterprises is of central importance to cope with the various social, economic and environmental challenges. In addition to political actions, economic approaches are necessary to address the most urgent global problems. Therefore, this paper contributes to the development of theoretical approaches to analyze how social enterprises create and maintain (sustained) competitive advantage and thus contributes to the current understanding of longterm success of social enterprises.

To answer the question “How do social enterprises create competitive advantage?”, we conducted a qualitative research design and conducted several in-depth, semi-structured interviews with social enterprises. Theoretically, this paper is based on the resource-based theory, which is applied to evaluate which firm resources of SE´s can be exploited to create (sustained) competitive advantage.

2. Sustained Competitive Advantage and Social Enterprises

Different from the structural approach (Porter, 1980; Porter, 1985), the resources-based theory (RBT), explains competitive advantage, in particular sustained competitive advantage, based on the internal resources of a firm (Barney, 1991; Rumelt 1984; Wernerfelt, 1984). Thus, competitive advantage depends on the unique resources and capabilities a firm possesses, not just on the assessment of environmental opportunities and threats (Barney, 1995). Therefore, competitive advantage is achieved by implementing a value creating strategy based on the utilization of the firm’s specific resources (Barney, 1991). In this context, competitive advantage is sustained only if competitors are not able to duplicate the benefits of the value creating strategy (Rumelt, 1984; Barney, 1991).

These firm resources and capabilities are defined as attributes that enable organizations to conceive and implement value-generating strategies (Learned et al., 1969; Porter, 1981; Barney, 1991). Scholars have classified the numerous resources and capabilities into a variety of categories (Afuah & Tucci., 2001; Barney, 1995; Lee, 2001; Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2004). However, for the purpose of this paper, the numerous possible firm resources and capabilities are classified into seven categories: physical, financial, human, organizational, legal, informational and relational (Seppänen & Mäkinen, 2007).

According to Seppänen and Mäkinen (2007), physical resources and capabilities relate to geographic location, land, realty, machinery, equipment and raw materials. Financial resources and capabilities include the total amount of capital as well as other financial instruments. Human resources and capabilities include employee related attributes, networks, experience and education. Organizational resources and capabilities relate to firm owned assets such as structure, processes, brand, but also corporate culture, routines and reputation. Legal resources and capabilities reflect firm assets, which are protected by property rights. These include patents, trademarks, licenses, copyrights and others. Informational resources and capabilities are comprised of “collective, explicitly expressed knowledge” (Seppänen & Mäkinen, 2007, p. 9), which can be technically stored. Relational resources and capabilities include the relationships between the firm and its various external stakeholder.

The resource-based theory is based on two central assumptions: resource heterogeneity and immobility (Barney, 1991). Assuming the opposite, i.e. perfectly homogenous and mobile resources, implies that all firms have access to the same resources. This circumstance would allow competitors to replicate every value creating strategy and therefore achieve the same results as the firm. As a result, no firm can achieve sustained competitive advantage with perfectly homogeneous and mobile resources. However, it can be expected that in most industries resources can be described, at least to some degree, as heterogeneous and immobile (Barney, 1991; Barney & Clark, 2007).

Barney (1991) recognizes that not all resources have the potential to create a sustained competitive advantage for the firm. In order to hold the potential of sustained competitive advantage, a firm’s resource must have four attributes: (1) it must be valuable, (2) it must be rare, (3) it must be inimitable and (4) it must be non-substitutable (Barney, 1991; Barney, 1995; Madhani, 2010; Talaja, 2012). However, it is stressed that a firm’s resource has to be at least valuable and rare to create a temporary competitive advantage for the firm, but, nevertheless, to create sustained competitive advantage, a firm’s resource also has to be imperfectly imitable and not substitutable (Talaja, 2012). The attributes are explained in more detail below.

- Valuable: A firm’s resource is considered valuable if it is able to exploit opportunities and/or to compensate for threats (Barney, 1991; Talaja, 2012). Therefore, the strategic value is of particular importance for the firm (Madhani, 2010), i.e. the resource enables a firm to create and execute strategies which are intended to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of the firm (Talaja, 2012).

- Rare: A firm’s resource is considered to be rare if current and potential competitors do not possess such a resource (Barney, 1991; Barney, 1995; Madhani, 2010). However, it is difficult to specify how rare a resource must be to create competitive advantage. According to Barney (1991), a resource can be considered rare if the total number of firms that own that resource is lower than the total number required to create a perfect competitive dynamic in an industry.

- Inimitable: A firm’s recourse is considered to be insufficient imitable if firms who do not own the resources are not able to acquire, imitate or copy the resource (Barney, 1991; Barney, 1995; Madhani, 2010). Within the resource-based theory, firm resources can be insufficient imitable for one of three (or a combination of) reasons: (a) acquisition of resource is difficult, (b) the causality between the resource and the firms sustained competitive advantage is ambiguous and/or (c) the resource is highly complex (Barney, 1991; Madhani, 2010).

- Non-substitutable: A firm’s resource is non-substitutable if the resource cannot be replaced by a similar alternative resource (Barney, 1991; Barney, 1995; Madhani, 2010). Barney (1991, p. 111) defined similar alternative resources as “strategically equivalent”, which “can be exploited separately to implement the same strategies”. Hence, competitors are unable to create and implement a strategy with different resources but achieve the same results as the firm.

After defining the attributes of the resources necessary to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage for a firm, the causal relationship between the attributes and the competitive advantage, respectively sustainable competitive advantage, is outlined. In addition, the importance of the organizational environment is added.

The question whether or not a firm’s resource is valuable or not can be confirmed by whether the resource can be used to increase efficiency and/or effectiveness of the firm. In this context, valuable resources can be used to decrease cost (Barney, 1986; Peteraf, 1993), create and execute new strategies (Barney, 1991), or improve customer satisfaction (Bogner & Thomas, 1994; Verdin & Williamson, 1994). Thus, a resource is valuable if it can be exploited to improve firm performance relative to competitors. Consequently, if a non-valuable resource is exploited, this circumstance will most likely decrease effectiveness and/or efficiency and therefore lead to below-average economic performance and create a competitive disadvantage (Barney & Clark, 2007).

After a resource is considered valuable, it is necessary to determine whether the resource is distributed homogenously or heterogeneously among all competing firms (Barney, 1995; Barney & Clark, 2007). In fact, a resource must be valuable and rare to potentially be a source of a temporary competitive advantage. However, if a valuable resource is homogenously distributed and commonly available (not rare), it may be a source of competitive parity (Barney & Clark, 2007). Thus, resource heterogeneity implies differences in firm resource endowment. According to Helfat and Raubitschek (2000), several factors account for the differences in firm resource endowment: time of market entry, systems of knowledge and learning as well as product sequencing.

In accordance with Barney (1991), valuable and rare resources can generate a temporary competitive advantage. However, the degree of competitive advantage is dependent upon the imitability of the resource. If the resource is perfectly imitable, i.e. each market participant can acquire, imitate or copy the resource without significant effort, then only a temporary competitive advantage can be achieved (Mata et al., 1995). “The observation that valuable and rare organizational resources can be a source of competitive advantage is another way of describing first-mover advantages accruing to firms with resource advantage” (Barney, 1991, p. 107). However, only insufficient imitable resources can be a source of sustained competitive advantage.

In addition to the requirement of inimitability, firm recourses have to be non-substitutable to be a source of sutained competitive advantage (Barney, 1991; Barney, 1995). Thus, Barney (1991) follows the reasoning of Lippman and Rumelt (1982) and Rumelt (1984), who define sustained competitive advantage as an advantage that continues to exist after efforts to duplicate have ceased. This, however, does not imply that sustained competitive advantage exists permanently. Barney (1991) argues that unanticipated changes in the economic environment or industry can nullify any source of sustained competitive advantage. Therefore, a sustained competitive advantage can only be achieved if resources are valuable, rare, inimitable and nonsubstitutable.

Furthermore, Barney (1995) states that the potential of the firm to achieve sustained competitive advantage also depends on the corporate environment, i.e. the organization of the firm, including reporting structures, management control systems, and compensation policies. “These components are referred to as complementary resources because they have limited ability to generate competitive advantage in isolation” (Barney, 1995, p. 56). However, these complementary resources form the organizational framework of the firm, and therefore enable the firm to best exploit its resources and to gain a sustained competitive advantage. Thus, a firm can be considered a bundle of resources (Penrose, 1959).

According to the resource-based theory, firms compete on commercial terms in a competitive market environment (Peteraf, 1993; Chatain, 2011), and the value creation is reflected in the generated returns of the firm (Peteraf, 1993). Social enterprises, however, also pursue social objectives in addition to their commercial activities. In the literature, this circumstance is generally referred to as the pursuit of a dual mission, that is, combining a social purpose while engaging in commercial activities to achieve financial sustainability (Battilana et al., 2015; Dohrmann et al., 2015; Pache & Santos, 2013; Saebi et al., 2018). By pursuing a dual mission, social enterprises are a classic example of hybrid organizations, obliterating the conventional categories of private, public and non-profit organizations (Battilana et al., 2015; Doherty et al., 2014; Jay, 2013; Pache & Santos, 2013; Tracey et al., 2011). Although social enterprises appear in different organizational forms (Saebi et al., 2018), a common denominator is the focus on two categories of constituents: the beneficiaries of their social objectives and the customers of their commercial activities.

Saebi et al. (2018) categorized social enterprises based on the level of integration of beneficiary participation and the level of integration between social and commercial activities. First, a distinction is made whether the social value is created with or for the beneficiaries, second, the relationship between the commercial activities and the social objectives is considered. As a result, Saebi et al. (2018) define the following four typologies of social enterprises:

- Two-Sided Value Model: Commercial activity cross-subsidizes social objective. Beneficiaries are not involved in social or commercial value creation; they are solely recipients of the products and/or services.

- Marked-Oriented Work Model: Beneficiaries are employed to create products and/or services. The social enterprise participates in commercial market activities.

- One-Sided Value Model: Beneficiaries are paying customers. Social value is created through commercial activity.

- Social-Oriented Work Model: Beneficiaries are employed as well as paying customers. Commercial and social value is created by and for beneficiaries.

According to this typology, every social enterprise engages at least partially in some commercial activities. Therefore, social enterprises, just as any other organization must grow into “sustainable and viable organizations by acquiring valuable resources and developing capabilities that will maximize their resources’ utility” (Bacq & Eddelston, 2016, p. 589). As such, they must operate in a competitive environment and compete with public sector, for-profit organizations and traditional non-profit organizations (Borzaga & Solari, 2001). However, social enterprises have considerable resource constraints, as their social objectives are often prioritized over their commercial activities (Desa & Basu, 2013). For these reasons, it is particularly important to identify the resources that represent a potential source of sustainable competitive advantage for SE´s.

3. Methodology

Aim and Design

This study explores which resources social enterprises exploit to create sustained competitive advantage. For this purpose, social enterprises in the Hochtaunus Area, Germany, were interviewed. A qualitative research design was chosen to better understand what resources SE´s exploit and how these resources are organized to create a sustained competitive advantage.

Sample

The sample is composed of eightsocial enterprises, organizations that primarily achieve a social purpose while engaging in commercial activities (Battilana et al., 2015; Saebi et al., 2018), based in the Hochtaunus Area in Germany. The social enterprises are operating in various sectors, including education, tourism, finance, retail and others. The companies surveyed are operating between 4 and over 20 years. 50 percent of the social enterprises are registered as registered voluntary associations, another 37,5 of the surveyed social enterprises are organized as a non-profit limited liability companies, and the last 12,5 percent are registered as companies with limited liability.

Financially, the social enterprises relay on two income streams: Between 20 and 80 percent of the revenue are generated through marked-based activities, and the remaining revenue share is generated through donations. Depending on the legal status of the companies, donations can be provided either by private sector companies or foundations, or through state subsidies or tax reductions. In addition, the legal status of the considered enterprises also has a considerable influence on the employment structure. Thus, registered voluntary associations can partly rely on volunteers, whereas (non-profit) limited liability companies may only employ regular employees. This is also reflected in the employment structure for the considered sample. Managing directors, founders or employees of senior management were surveyed.

The social enterprises were identified through in-depth research in business registers of the different cities and districts of the Hochtaunus Region. The organizations were selected on the basis of two relevant criteria derived from the definition of social enterprises. First, the organizations had to pursue a social purpose as their primary activity. Second, at least a part of the organizations revenue had to result from commercial activities. Based on these criteria, a total of 20 potential social enterprises were identified in the various company registers.

The classification of the organizations is based on the typology of Seabi et al. (2018). Accordingly, two organizations pursue a two-sided value model, in which the social objective is cross subsidized by commercial activities (Saebi et al., 2018). In addition, four of the analyzed organizations operate the one-sided value model. The last two organizations apply a social-oriented work model; therefore, commercial and social value is created by and for beneficiaries (Saebi et al., 2018).

Data Collection

Data was collected from the participants via in-person and phone/video (due to the restrictions of the pandemic) semi-structured interviews (40 % response rate). We followed the recommendations of Dresing and Pehl (2015) for effective interview design.

In the first part of the interview, the participants were asked about the organization, the structure of the enterprise and the firm’s resources. The purpose of these questions was to ensure an interesting start for the participants and to obtain the necessary information about the company for the typographical determination. The second part of the interview was based on the questions derived from Barney and Clark (2007). In this section, the resources identified in the first part of the interview were examined to determine whether they meet the VIRO criteria, defined in the resource-based theory, and could therefore be a source of sustainable competitive advantage. The third part of the interview dealt explicitly with the possible VIRO resource. Here the focus was on the question of whether this resource is only relevant because the organization is a social enterprise, or whether this resource would also be essential if the company were to pursue a purely commercial strategy. The last and fourth part of the interview consisted of demographic questions about the participant and the organization.

We conducted a pre-test to evaluate the quality of our interview script. For this purpose, the interview script was discussed with several expert scholars in the field of entrepreneurship to ensure that the interview script was consistent and that all questions were meaningful and organized. Based upon the feedback, some questions were rephrased. To ensure that our interview partners were prepared with all necessary information for the interview, we sent a short version of the interview script to all interview partners in advance.

Data Analysis

The data analysis was based on a content analysis approach as described by Mayring (2014) and was performed using three main sections: paraphrasing the content-bearing passages, followed by generalizing the paraphrased content, and finally grouping the new statements in a system of categories. Within the first main section of the analysis, all text segments that were not substantial passages were removed, such as decorative text, repeated segments and clarifying phrases. Second, substantive text passages were translated into a uniform language and third, they were converted into a grammatical short form.

Next, the paraphrased content was generalized to the desired level of abstraction. Any paraphrased passages already at the desired level of abstraction remained. Subsequently, paraphrased passages with the same content were removed. Similarly, paraphrased passages that were not considered essential in terms of content at the new level of abstraction were eliminated as well. Thereupon, paraphrased passages with the same or similar statements were combined into one statement.

Finally, the paraphrased statements from the individual interviews were combined. The combined and paraphrased statements were then categorized. The results were compared with the original material to ensure completeness and accuracy.

For the evaluation and paraphrasing of the interviews MAXQDA (software for qualitative analysis, VERBI GmbH) was used. The study was approved by the accadis Research Committee and Head of accadis Institute of Entrepreneurship.

4. Results

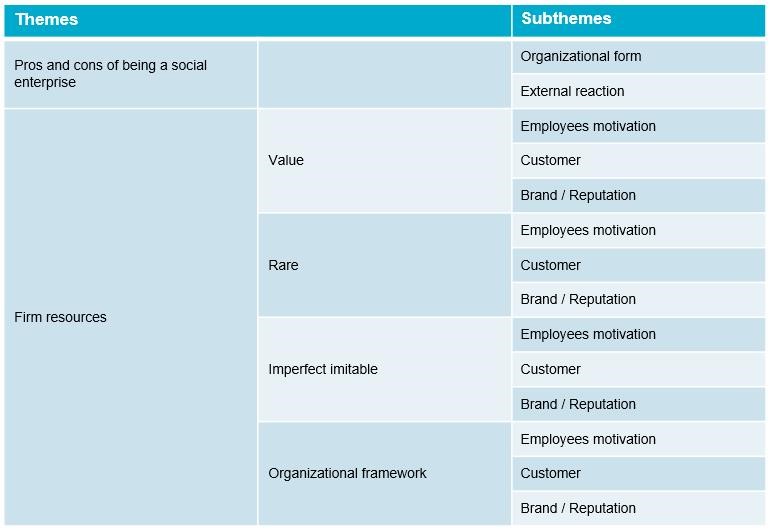

Overall, two main themes emerged through the analysis: Pros and cons of being a social enterprise and firm resources. The latter is further divided into four subsections which, according to the resource-based theory, correspond with the VIRO criteria: value, rare, insufficient imitable and organization. There are additional sub-themes to these topics that describe variations in the participants evaluation and experience.

Pros and Cons of Being a Social Enterprise

According to the participants experience, social enterprises do not necessarily have an advantage – in the economic sense – simply because they pursue a social purpose. The participants always distinguished between tax and legal advantages resulting from the legal form of the organization and other advantages, such as special contracting conditions with banks or suppliers and other partners. The former, legal and tax advantages associated with certain organizational forms, were considered very positive by the participants. In Germany, these advantages particularly concern organizations with the legal form of a registered voluntary associations and a non-profit limited liability company.

So, there are obvious advantages, as a non-profit organization has certain tax and legal advantages. (IP1)

When considering other advantages, the participants’ experience was more differentiated. On the one hand, certain advantages in the acquisition of partner companies and networking were acknowledged. This is particularly evident in the case of the well-known partner organizations with which the social enterprises cooperate. Furthermore, the participants noted that cooperation with commercial enterprises is generally very advantageous.

We definitely have advantages. Actually, everyone likes to work with us, whether it’s a bank, a service provider, an IT service provider or a marketing agency. (IP5)

In contrast to the positive experiences, the participants also expressed concerns that the products and/or services offered by social enterprises are perceived as inferior or of minor quality. This perception – especially from partners and customers – can be attributed to the understanding of the price-quality relationship that is commonly observed in society. According to the PriceQuality Relationship, the perceived quality of a product and/or service depends on the price. Accordingly, a high price indicates high quality.

From the very beginning it was important to us to communicate to the public: our organization should not be evaluated as weaker or inferior. We are not just a small non-profit organization; we are working with some of the largest IT organizations and offer a great service. (IP1)

Although this perception – cooperating with leading and well-known commercial organizations acknowledges the quality of the products and/or services offered by social enterprises – is shared by all interviewees, the participants admit that this is a very one-dimensional perspective. According to the participants, economic and image aspects are more decisive for commercial enterprises to engage in a cooperation with social enterprises.

There is usually an economic reason for this. There is actually no one else who can do this work for these conditions. We mostly take over sorting and packaging work, which otherwise the companies would not or cannot do themselves. But if we receive the order because of our social orientation, I dare to doubt. (IP4)

Firm Resources

Value

A firm resource must be valuable, i.e. it has to be exploited to improve firm performance relative to competitors, to be a source of sustained competitive advantage. According to the participants, three resources of a social enterprise fulfill this requirement: Motivation of employees, customer and brand / reputation.

The motivation of the employees, but also of the founders, is seen as central for the survival, but also for the success of social enterprises. The participants noticed that the motivation – their own and of their employees – is intrinsic and driven by the desire to positively influence the world. The financial interest of the employees is subordinated to the desire to achieve good.

Our employees are people with convictions. (IP7)

I think a very valuable resource is our our will or our motivation to positively change something. (IP1)

According to the participants, another valuable resource for social enterprises is the customer. Thereby it depends on the typology of the social enterprise who is regarded as the customer. These can be, first, the beneficiaries themselves, who as paying customers receive products and/or services, or regular customers, who either cross-subsidize the social purpose by purchasing a product and/or service, or purchase products and/or services offered by SE´s that employ the beneficiaries. In all cases the customer is relevant, since only through this support – which, according to the participants, is based on the desire to bring about something positive, or to improve one’s own unfortunate situation – this is possible.

The customer is the link between the social and commercial goals of our organization. His attitude towards our organization determines our success. (IP3)

The last resource identified by the participants as valuable for social enterprises is the brand and/or reputation. This is particularly due to the positive association that customers and partners of social enterprises have with the brand and/or reputation.

So, we have a very good image. Our organization has an incredibly great brand, which has a very positive reputation. Accordingly, all doors are open for our organization. (IP4)

Rare

According to the resource-based theory, the resource must be rare among competitors to be a source of sustainable competitive advantage. According to the participants, this circumstance also applies to the motivation of employees and founders, which is not financial but social oriented. This is evident in the large number of volunteers and the often – compared to commercial companies – below-average payment of employees. The participants also stated that it is difficult to recruit new employees. This fact also shows that the motivation to work for social enterprises – and to accept the financial disadvantages associated with it – is rather rare among potential employees.

All employees work voluntarily and do not receive a single penny, unfortunately it is difficult to find such employees nowadays. (IP6)

This also applies, at least to some degree, to the customers of social enterprises. Here, the participants indicated that – due to the unique orientation of a social enterprise – the target group is generally limited. This is particularly the case for social enterprises, which, for example, employ the beneficiaries or directly target the beneficiaries as paying customers. These can be people with a disability, refugees or people within certain circumstances.

Well, the number of beneficiaries in our case is of course very limited

[…]. (IP2)

Also, with regard to the brand and the reputation of social enterprises, the participants are of the opinion that the social orientation of the organization is a unique characteristic. The social orientation promotes a positive attitude towards these organizations. For this reason, social enterprises are able to create an extremely positive corporate reputation or to create a positive image for the organization’s brand.

In the Frankfurt area, we are very well known for our social orientation and our work with disabled people. (IP8)

Insufficient Imitable

After a resource is considered both valuable and rare, the firm resource has to be insufficiently imitable as well, to be a source of sustained competitive advantage. This implies that the resource must be immobile and non-substitutable. Considering this, the participants confirmed that the motivation of employees, in particular of volunteers, is essential for the success. The participants confirm that the employees are not financially but socially motivated. Commercial companies can only compensate for this through considerable financial disadvantages, namely higher salaries, if at all. However, the participants acknowledge that the existing employees and volunteers could be recruited by other social enterprises or NGOs.

We need good and motivated volunteers; it doesn’t work otherwise. We are very proud of the fact that everyone comes and helps regularly. (IP6)

The participants emphasized that their organizations only address a very specific target group, with very specific needs. This specialization enables social enterprises to offer their products and/or services at a cost advantage over commercial enterprises. In addition, participants noted that commercial enterprises are often unable to address these specific needs of the beneficiaries.

It is a target group that is not considered immediately and is therefore rarely addressed. (IP2)

According to the participants, the development and establishment of a brand and/or reputation is expensive and requires a considerable amount of time. Furthermore, brands in particular are legally protected. Accordingly, a brand can only be purchased or replicated in another form.

Yes, definitely! Competitors would face a big cost disadvantage, because it is very expensive and time consuming to establish a new brand. (IP5)

Organizational Framework

According to the resource-based theory, the firm has to be structured in such a way that the firm’s resources can be exploited in the best possible way. The participants confirmed that the organizational framework of the firms is structured in such a way that the relevant resources can be exploited adequately. Furthermore, the participants stated that the organizational form is not a rigid unit but must be continuously adapted. Among other things, the structures are designed in such a way that employees can work self-responsibly and flexibly, the compensation systems are not exclusively based on monetary incentives and the development of the employees is the main priority. The aim of this organizational framework is to sustain the motivation of employees and volunteers.

We offer personnel development and provide various further education and training courses. (IP4)

Furthermore, the participants indicated that the organizational framework – particularly with regard to the legal form of social enterprises – is adapted to certain customer requirements. This applies in particular to institutional customers, who enjoy considerable legal and tax advantages due to the special legal forms of social enterprises.

If the beneficiaries are the customers, the organizational framework of social enterprises is very customer-centered, with the aim of continuously improving products and/or services

Product innovations or the expansion of the portfolio are always based on discussions with customers. (IP2)

However, current developments and trends are also represented by the organizational framework. According to the participants, digitization in particular has a considerable influence on the significance of the brand and/or reputation. The participants emphasized that this development in particular has had a significant impact on the relevance of resources, exploitation and organizational framework.

Therefore, we have to think about how to maintain the brand. Now we have to be present everywhere and consider how we want to be represented. (IP5)

5. Discussion

For an organization to earn excess returns, a sustainable competitive advantage is necessary (Dickinson & Sommers, 2012). Of course, this also applies to social enterprises; however, the goal is not to generate excess financial returns, but rather excess social value – or a balanced combination of both. Therefore, it is necessary to identify the relevant resources that represent a potential source of sustainable competitive advantage for SE´s. The participants identified the motivation of employees, the customers and the brand and/or reputation of the social enterprise as possible sources of sustained competitive advantage. According to the resource-based theory, these resources must be rare, valuable and inimitable, and must be organized in such a way that they constitute a potential source of sustainable competitive advantage (Barney, 1991; Barney 1995; Madhani 2010). Our analysis of the three potential VIRO resources has demonstrated that the motivation of employees, the customers and the brand and/or reputation can be potential sources of a sustained competitive advantage. In the following we will discuss this for the three considered resources:

Employee Motivation

As stated by Barney (1991, p. 106), “resources are valuable when they enable a firm to conceive of or implement strategies that improve its efficiency and effectiveness.” Through the intrinsic, non-monetary motivation of the employees, and through the employment of volunteers, social enterprises are able to realize considerable reductions in employee wages. However, since the performance of the employees is equal to the performance of employees of commercial companies, the work is performed more efficiently. Consequently, social enterprises can achieve the same output of employee performance as commercial enterprises with a lower input of financial resources. Accordingly, the motivation of employees can be considered a valuable resource.

The next attribute that a resource must meet to be a source of sustainable competitive advantage is rarity (Barney, 1991; Barney 1995). Many participants reported that it is becoming increasingly difficult to recruit new, socially motivated employees. This can partly be attributed to the fact that financial incentives in particular are an important factor in employee motivation (Yousaf et al., 2014). In addition, the participants noticed that especially in the social sector, the number of volunteers has stagnated for years, or even partially decreased. These statements are also confirmed by statistics on voluntary work in Germany from the Allensbach Institute for Public Opinion. Accordingly, the motivation of employees can be seen as both a valuable and a rare resource.

Thus, the socially oriented motivation of employees is a source of a temporary competitive advantage, however, in order to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage, it must also be inimitable, i.e. immobile and non-substitutable. Although this employee motivation can also be achieved by competitors, it can only be achieved at a financial disadvantage. Furthermore, since employee motivation is a highly complex resource, we argue that, in terms of the resourcebased theory, it is an inimitable resource.

As we have already stated in the results, the participants explained that the organizational framework of the organizations is designed and continuously adapted to ensure optimal exploitation of the most important resources. In particular the employee-centered alignment of the organization, especially the management structures, compensation systems and employee development, promote employee motivation. Accordingly, employee motivation can be classified as a VIRO resource, and can therefore be a source of sustained competitive advantage.

Customer

Depending on the typology of the social enterprises the customers are either the beneficiaries themselves, who as paying customers receive products and/or services, or regular customers, who either cross-subsidize the social purpose by purchasing a product and/or service, or purchase products and/or services offered by a social enterprise that employs the beneficiaries. Consequently, depending on the typology, the customer is either the recipient of the social value or the provider of the financial resources. Accordingly, the customer is an integral part and facilitates social enterprises to execute new strategies.

To answer the question of rarity, first the beneficiaries as paying customers are considered. In this case, due to the particular focus on a certain target group, the number of potential customers is generally limited. Therefore, in this case, the customer can be considered a rare resource. In the cases in which regular customers cross-subsidize the social purpose by purchasing a product and/or service, or purchase products and/or services offered by Se´s that employ the beneficiaries, the customer cannot be considered a rare resource.

In the further consideration of the customer we solely consider the beneficiary as the customer. In case the beneficiaries are paying customers, a high degree of immobility and nonsubstitutability can be assumed. We derive this from the general objective of social entrepreneurship: “identifying a stable but inherently unjust equilibrium that causes the exclusion, marginalization, or suffering of a segment of humanity that lacks the financial means or political clout to achieve any transformative benefit on its own” (Martin & Osberg, 2007, p. 35).

In cases where the business model is focused on the beneficiaries as customers, the organizational framework of the company is focused on the adaptation of products and/or services to the circumstances of the beneficiaries. Thus, the whole enterprise, in particular the creation of value, is oriented towards the customers and their special circumstances.

In summary, we conclude that the customer is a VIRO resource if the business model is focused on the beneficiaries as paying customers.

Brand / Reputation

The brand and/or reputation is a very valuable resource for social enterprises according to the participants. A positively associated brand and/or reputation enables social enterprises to adequately approach and address customers and partners. As a result, social enterprises are in a position to implement strategies that increase their effectiveness. Thus, the brand and/or reputation can be seen as a valuable resource.

A brand and/or reputation in general is not rare, but the specific brand and/or reputation certainly is. Assuming that the brand is protected by trademark law, it is unique and therefore rare. In addition, the primary social focus of these organizations is a unique characteristic. Accordingly, the social orientation promotes a positive attitude towards these organizations and therefore a positive reputation.

The protection of the brand by the trademark protection law contributes not only to the rarity but also to the inimitability of the brand. This protection prohibits competitors to use the trademark in any form, which makes the brand perfectly inimitable. However, the trademark can be substituted by building up a new, similar trademark with a similar image. However, this is highly cost- and time-intensive, which would cause financial disadvantages for competitors. The organizational framework, in particular management and communication systems are organized in such a way that the brand is always at the center of the organization’s activities. The focus is on communication with customers and other stakeholders via the organization’s brand. The product and/or service is only indirectly promoted.

Accordingly, we conclude that the brand and/or reputation is a VIRO resource. Thus, the three mentioned resources – employees motivation, customers and brand / reputation – can be a source of sustained competitive advantage.

6. Conclusions

An overall conclusion from this preliminary interview study was that social enterprises, just as any commercial firm, implement value creating strategies – to achieve both, social and financial goals – that cannot be implemented or duplicated by any current competitor, and thus creating a sustained competitive advantage. We identified the motivation of the employees, the customer as well as the brand and/or reputation of SE´s as potential sources of sustained competitive advantage. The implications of this study are, on the one hand, that social enterprises have neither advantages nor disadvantages over commercial enterprises due to their social orientation, on the other hand, they can gain a sustained competitive advantage by exploiting their firm resources.

Although the study covered a wide range of industries, we did not differentiate between the different types of social enterprises. For this reason, we suggest that further research should examine whether there is a dependency between the typology of the social enterprise and the possible VIRO resources. For example, we have excluded the resource “customer” as a source of sustainable competitive advantage for social enterprises that cross-subsidize the social mission through a commercial activity. In our opinion, it is also interesting to examine the extent to which potential VIRO resources differ between social enterprises and commercial enterprises, or between social enterprises and CSR programs of commercial enterprises. Furthermore, the present study refers exclusively to social enterprises in the Hochtaunus region, Germany. We consider it as valuable to examine whether the geographical location of social enterprises has an influence on potential VIRO resources. In general, we recognize a great need for more research in the area of competitive advantage of social enterprises.

References

- Afuah, A., & Tucci, C. L. (2001). Internet Business Models and Strategies. Text and Cases. McGraw‐Hill.

- Barney, J. B. (1986). Strategic factor markets: Expectations, luck, and business strategy. Management Science, 32(10), 1231–1242.

- Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

- Barney, J. B. (1995). Looking inside for competitive advantage. Academy of Management Executive, 9(4), 49–61.

- Barney, J. B., & Clark, D. N. (2007). Resource-Based Theory – Creating and sustaining competitive advantage. Oxford University Press.

- Battilana, J., & Dorado, S. (2010). Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1419–1440.

- Battilana, J., Sengul, M., Pache, A. C., & Model, J. (2015). Harnessing productive tensions in hybrid organizations: The case of work integration social enterprises. Academy of Management Journal, 58(6), 1658–1685.

- Bogner, W. C., & Thomas, H. (1992). Core competence and competitive advantage: A model and illustrative evidence from the pharmaceutical industry. BEBR faculty working paper; no. 92–0174.

- Borzaga, C., & Solari, L. (2001). 19 Management challenges for social enterprises. The emergence of social enterprise, 4, 333.

- Bacq, S., & Eddleston, K. A. (2018). A resource-based view of social entrepreneurship: how stewardship culture benefits scale of social impact. Journal of Business Ethics, 152(3), 589–611.

- Chatain, O. (2011). Value creation, competition, and performance in buyer-supplier relationships. Strategic Management Journal, 32(1), 76–102.

- Desa, G., & Basu, S. (2013). Optimization or bricolage? Overcoming resource constraints in global social entrepreneurship. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 7(1), 26–49.

- Dickinson, V., & Sommers, G. A. (2012). Which competitive efforts lead to future abnormal economic rents? Using accounting ratios to assess competitive advantage. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 39(3–4), 360–398.

- Doherty, B., Haugh, H., & Lyon, F. (2014). Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management reviews, 16(4), 417–436.

- Dohrmann, S., Raith, M., & Siebold, N. (2015). Monetizing social value creation–a business model approach. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 5(2), 127–154.

- Jay, J. (2013). Navigating paradox as a mechanism of change and innovation in hybrid organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 56(1), 137–159.

- Learned, E. P., Christensen, C. R., Andrews, K. R., & Guth, W. D. (1969). Business policy. Irwin.

- Lee, C.‐S. (2001). An analytical framework for evaluating e‐commerce business models and strategies. Internet Research: Electronic Networking Applications and Policy, 11(4), 349–359.

- Ma, H. (2000). Competitive advantage and firm performance. Competitiveness Review, 10(2), 15–32.

- Madhani, P. M. (2010). Resource based view (RBV) of competitive advantage: an overview. Resource Based View: Concepts and Practices, Pankaj Madhani, ed, 3–22.

- Maretich, M., & Bolton, M. (2010). Social enterprise: from definitions to developments in practice. European Venture Philanthropy Association Knowledge Centre.

- Martin, R. L., & Osberg, S. (2007). Social entrepreneurship: The case for definition.

- Mata, F. J., Fuerst, W. L., & Barney, J. B. (1995). Information technology and sustained competitive advantage: A resource-based analysis. MIS Quarterly, 487–505. 29

- Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution.

- Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2004) An ontology for e‐Business models. In W. Currie (Ed.) Value creation from e‐business models. Butterworth‐Heinemann.

- Penrose, E. (1959). The theory of the growth of the firm. John Wiley and Sons.

- Peteraf, M. A. (1993). The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 14(3), 179–191.

- Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive strategy. Free Press.

- Porter, M. E. (1981). The contributions of industrial organization to strategic management. Academy of Management Review, 6(4), 609–620.

- Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive strategy. Free Press.

- Pache, A. C., & Santos, F. (2013). Inside the hybrid organization: Selective coupling as a response to competing institutional logics. Academy of Management Journal, 56(4), 972–1001.

- Rumelt, R. P. (1984). Toward a strategic theory of firm. In R. Lamb (Ed.), Competitive Strategic Management (pp. 556-570). Prentice Hall.

- Ryder, P., & Vogeley, J. (2017): Telling the impact investment story through digital media: an Indonesian case study. Communication Research and Practice, 4(4), 375–395.

- Saebi, T., Foss, N. J., & Linder, S. (2019). Social entrepreneurship research: Past achievements and future promises. Journal of Management, 45(1), 70–95.

- Talaja, A. (2012). Testing VRIN framework: Resource value and rareness as sources of competitive advantage and above average performance. Management-Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 17(2), 51–64.

- Tracey, P., Phillips, N., & Jarvis, O. (2011). Bridging institutional entrepreneurship and the creation of new organizational forms: A multilevel model. Organization Science, 22(1), 60–80.

- Verdin, P. J., & Williamson, P. J. (1993). Core competence, competitive advantage and market analysis: forging the links. Fontainebleau, France.: INSEAD.

- Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the Firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171–180.

- Yousaf, S., Latif, M., Aslam, S., & Saddiqui, A. (2014). Impact of financial and non financial rewards on employee motivation. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 21(10), 1776–1786.