Abstract

In this study, we examined how to manage start-ups experiencing a high level of uncertainty in emerging markets, and what are the principles of agile strategic learning in a start-up? Pragmatic literature on start-ups has put significant emphasis on agility and quick learning in managing a start-up, but scientific literature is scant in this field. In this study, we conceptualized agile strategic learning as start-ups’ capability to reflect on their experiences with existing hypotheses and reframe them in line with new insights about emerging markets and customers. Thus, agile strategic learning is a continuous transformative learning process where start-up teams rapidly experiment with new things, aiming to learn by testing existing beliefs, plans, and models. The agile strategic learning approach creates a competitive advantage for start-ups. We recommend further research on the methods and practices that promote the rate and agility of learning in managing start-ups.

Keywords: start-up, entrepreneurship, agile learning, strategy, new business development

1. Introduction

The need for continuous transformative learning in start-ups is huge. From previous research (e.g. Aldrich & Yang, 2014; Ries, 2010; Toft-Kehler et al., 2014), we already know that start-ups need to continually learn from emerging markets. They typically operate in a market where uncertainty is very high (Paternoster et al., 2014). This is because the market is still emerging, products or services are new to customers, and new solutions are disrupting the existing business (Valkokari et al., 2018). A management challenge for start-ups is that the value proposition of a start-up is not yet properly confirmed by potential customers (Ries, 2010). In this study, we define a start-up as a company that aims with a novel solution to emerging markets or it develops a novel solution for the existing markets.

The establishment of a conventional business is not a start-up in the true sense of the word, although it is also considered entrepreneurship. Setting up a company for an existing market is a less complicated business development process than entering into an emerging or completely new market. Start-ups often deal with radical innovations, as they aim to create novel solutions for markets or enter into an existing market with a novel strategic solution. Assink (2006) stated that it is more difficult to estimate market acceptance and potential with a radical innovation than with a conventional innovation or service. Breaking into a mature market often requires rapid market entry with excellent execution capability – the ability to get ahead and stay there with constant innovation. However, emerging markets create new business opportunities for new service providers (Alamäki et al., 2018), such as start-ups.

We also know that start-ups need to continuously learn from customer behaviour (York & Danes, 2014). Pervasive customer understanding is particularly important for start-ups, as paying customers create a functioning market where these start-ups can survive (Roundy, 2018). This means that start-up entrepreneurs need to identify a “broken process” or any other latent problem, need, or desire which is not fulfilled and for which several customers are willing to pay.

Quick and continuous organizational learning provides a competitive advantage for start-ups (Aldrich & Yang, 2014; Baltrūnaitė & Sekliuckienė, 2020). Although the literature on entrepreneurship and new business development provides rather broad insights into start-up management, research on organizational learning in the context of start-ups is scarce (Baltrūnaitė & Sekliuckienė, 2020). Furthermore, literature on strategic management has emphasized customer and market understanding, and less is known about how start-ups could continuously learn to strengthen their agility in hard international competition and survival. Therefore, a greater understanding is needed concerning how start-ups could foster their learning processes, especially from the perspective of strategic management. This study contributes to he aforementioned research gaps, as pragmatic literature has put significant emphasis on the agility of start-up management and learning, but to the best of our knowledge, scientific literature on this field is scant.

This study focused on the principles of strategic development and management from an individual and organizational learning perspective. We reviewed the strategic management challenges by conducting a scientific literature review, and using this review, we created a model of agile strategic learning in a start-up. The agile strategic learning is a process where entrepreneurs and management of start-ups continuously analyse and reflect their business experiences or observations for reframing their business understanding through strategic goals and initiatives. The research method employed in this study was conceptual research (Meredith, 1993). We put special focus on agile learning of teams that form a key success factor for start-ups. Thus, we aimed to create theoretical model related to the principles of continuous learning in a start-up.

2. Theoretical framework for start-up’s management and learning

2.1 Three main ways to create a new business

In a start-up, the product or service is new to customers or the business model is not well established among buyers and sellers. If a company tries to access an existing market with a completely new business model, it is also referred to as a start-up. For example, low-cost airlines began to compete for the customers of trains and buses, not the customers of existing airlines. Thus, they created a new market segment with a new solution. The following business cases illustrate how uncertainty about new business development occurs (see, e.g., Ries, 2010):

• Customer is unknown – solution is unknown (new market and new solution or business model).

• Customer is known – solution is unknown (old market, but new solution or business model).

• Customer is known – solution is known (old market and old product, service, or business model).

The first business case illustrates situations where market is emerging. The second case describes old markets where start-ups aim with new solutions or business model. The last business case represents old market where products, services and business models are established and known. These business cases show that a start-up can compete with two types of innovations: (i) product or service innovation and (ii) business model innovation (Ghezzi & Cavallo, 2018; Rosenbusch et al., 2011). Rosenbusch et al. (2011) found that small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) benefit more from business model innovations or strategic orientation to innovation than from purely product or service innovations. In addition, Atalay et al. (2013) reported that, unlike technological innovation, organizational or marketing innovation did not affect firm performance. Thus, product or service innovations create a competitive advantage if they are based on new technology, whereas organizational or marketing innovations seem to have little impact on the actual competitive advantage of companies in general. The relationship between creativity and innovation was strong at the individual level (Sarooghi et al., 2015); thus, start-ups could benefit from creative persons, although creativity was not found to be a significant factor in technological innovation. Namely, Sarooghi et al. (2015) found that the relationship between creativity and innovation was weaker in high-tech companies than in traditional ones.

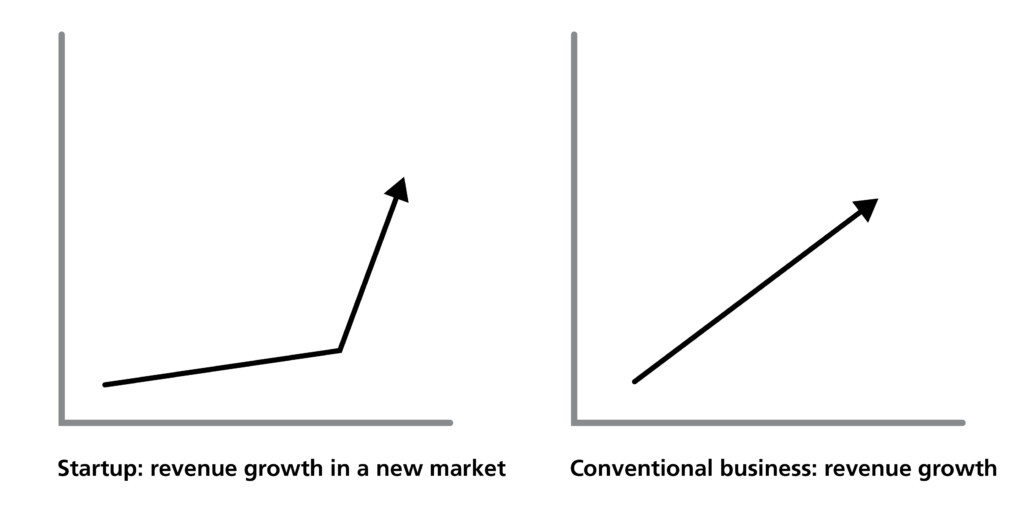

The founding of a start-up differs from that of a conventional business in terms of revenue development (Figure 1). At the beginning, the revenue is low in a start-up, as the market is opening. First, customer cases are pilot projects, and second, customers are typically innovators and early adopters who like to learn about new opportunities. For example, the shape of game company Rovio’s revenue development from 2010 to 2012 is like a hockey stick when the revenue climbed from 1.5 to 150.0 million euros. Game company Supercell experienced even a higher rise in its revenue. Eniram Oy, a Finnish B2B software company, grew its revenue from approximately 0.8 to 8.0 million within 4 years from 2009 to 2012.

2.2 Start-ups and customer needs

Planning business for emerging or totally new markets differs from planning a conventional business. Thus, start-up pragmatists (e.g. Blank, 2020; Ries, 2010; Ryan, 2016; Tjan, 2012) have questioned the traditional business plan: Is it worth creating a detailed multiannual plan for a business in which customers and markets do not even know yet what they want? In Mike Tyson’s words, “everyone has a plan until they get their first punch in their faces”.

There are numerous examples of businesses in the world, where supply chains and production lines were built first and then good salespeople were hired, but the sales have not started to fly (Cbinsights, 2020; Song et al., 2008). Song et al. (2008) stated that after 4 years, only 36 percent of SMEs (with more than five employees) had survived, whereas after 5 years, the survival rate was 22 percent in US-based companies. The reason for failure was not poor salespeople, products, or services, but the immature market. Instead of preparing extensive business plans, start-up entrepreneurs and most venture capitalists recommend the agile or lean business development process (Edison et al., 2015; Ghezzi & Cavallo, 2018), where founders need to start learning from markets with the help of minimum viable products. This means that it is not wise to do heavy investments before founders have identified the real demands of markets.

According to the lean start-up approach (Ries, 2010), start-ups need to develop an understanding of customer latent needs and motivation to pay for new products or services. This assists them in creating a cost-effective solution and repeatable marketing and sales models. After the customer development and learning phases, fixed costs can be increased; for example, more employees can be hired, fancier premises can be rented, and investment in service production capacity can be started. Thus, customer-focused business development is a strategic innovation process that includes the building of marketing and sales-oriented capabilities in addition to the process of developing new products or services.

Entrepreneurs usually have personality dimensions – such as self-efficacy, achievement, and entrepreneurial orientation (Frese & Gielnik, 2014) – that help them succeed in solving ill-defined business problems in uncertain markets. In addition to good performance cognitions (Uotila, 2015), they have social capital and network diversity (Stam et al., 2014) that they need in hunting new customers in emerging markets.

2.3 The role of strategy and strategic progress in start-ups

Start-ups operate in a constantly changing and turbulent operating environment, which is why they should be strategically agile. More importantly, it should be emphasized that their strategic development is also a learning process. New business development in volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous environments requires a continuous cycle of monitoring, reframing, and implementation (i.e. continuous learning). The Japanese have sometimes described the construction of a new business as shooting arrows in the fog. A muted sound is heard from the fog, which indicates the direction the next arrow should be aligned to in order to hit the centre of the target. “Start-up” is such a continuous strategic learning environment. This challenge is increasingly evident in the whole business community. Although constant change is a permanent state in society, forecasting future demands is increasingly difficult. The ability to learn from experience, and from customers in particular, has become critical for all companies. Studies from larger companies reflect the same, as human resource leaders are most concerned about how to identify and assess the competence gaps of employees with regard to achieving business objectives (LinkedIn, 2019).

According to one definition, “strategy” refers to the objective, competitive advantage, and scope (Collis & Rukstad, 2008). The core of Rumelt’s (2011) strategy includes diagnosis, guiding policies and principles, and coherent actions. Teece’s (2007) dynamic capabilities consist of sensing, seizing the opportunity, and, on the contrary, continuous allocation of tangible and intangible resources. Doz and Kosonen (2008) emphasized the company’s strategic sensitivity, leadership unity, and resource fluidity. Sensing, diagnosis, and strategic sensitivity mean curiosity and desire to constantly learn new things. The ability to seize the opportunity requires orientation to action and agility. In strategically progressive start-ups, scenario planners become scenario learners. Experimentation and iteration are typical approaches to technology start-ups. Nevertheless, according to studies on A/B testing of start-ups (Koning et al., 2019), surprisingly few companies make use of low-threshold cheap experiments and testing tools.

Sometimes even failures are celebrated in start-ups. This ideology seeks to highlight the importance of the atmosphere and, in fact, an opportunity to learn all the time – make a pivot or persevere. Supercell, for example, initially focused on Facebook games, but after learning more about the market – especially competitors – it changed its strategy and focused on tablet-based games. Tablets and touchscreens were just the emerging (i.e. representing the opening) market.

Previous research (e.g. Blank, 2020) showed that learning from sustainable business models is critical for start-ups. Blank (2020) highlighted the need to find a repetitive customer case and a sales model for start-ups. Only this way, a start-up can find a functional and replicable business and earning model. Effective strategy execution capability would not help if customers and markets are not ready to buy. Unlike in start-ups, the success of conventional companies depends more on the capabilities of executives. For example, the founding of a cleaning or construction company operating with a traditional business model is strongly dependent on its executive capacity to construct and implement a business plan. Customer segments and their specific needs and selling solutions are already familiar to founders. Thus, there is not much uncertainty about customer expectations and behaviours and market maturity.

2.4 Start-ups’ first customers are early adopters, but they need a reason to buy

A start-up competes in a market where even customers do not yet recognize their latent needs or identify solutions. In addition, the problem, need, or desire for which a start-up is developing solutions must be significant enough for customers to sacrifice their time and spend money on it. Thus, a start-up cannot create successful business if the solution is only “a little better” than the previous solution. Customers need to have a “compelling reason” to buy (Moore, 1991; Stirewalt, 2017). In fact, the new solution must provide a value proposition that is so significant that there is no rationale for customers to skip the purchase opportunity. Therefore, it is difficult to get a new business to fly if the new value proposition is just a little better than the existing solutions.

All customers do not begin to buy and use new services at the same time (Hallikainen et al., 2019a), but they fall into different customer segments according to their purchase behaviours (Hallikainen et al., 2019b). The first customers of start-ups are typically innovators and early adopters (Moore, 1991; Rogers, 1995). They often buy because they want to learn or raise their own status, or they are interested in new technological features and solutions. However, according to Rogers’ (1991) research, only 15 percent of customers fall in this category, and start-ups often have difficulties finding them without huge marketing and sales effort. When a market is developing, pragmatic buyers begin to buy, but their motivation differs from innovators and early adopters. They buy because of business benefits; they are less interested in new technological features, and they value reference cases (Moore, 1991). However, competition in the market grows while the market is gaining more maturity. Furthermore, individuals begin to buy new products or services before organizations do (Wood & Li, 2005). Thus, it is important to recognize whose needs the start-up is targeting to meet – the needs of only a single person in an organization or those of a team, unit, or large organization. However, the potential target group needs to be large enough.

2.5 Teams and learning ability

Instead of a product or service, a start-up or any company should immediately analyse the initial idea in relation to the customers, market, distribution channels, and business model (Blank, 2020; Roundy, 2018). Thus, organizational learning plays a crucial role in the survival of start-ups (Sekliuckiene et al., 2018). Start-ups adopt a behavioural learning style rather than more formal cognitive or action learning practices (Baltrūnaitė & Sekliuckienė, 2020). According to Balfour (2017), the problem to be solved by a start-up team and an equivalent possibility lie primarily in the market and target groups, not in the market-product fit itself. In addition, the product must adapt to an existing product-channel fit. Further, the distribution channel must be compatible with the channel-model fit. Finally, the business model must be compatible with the target market (model–market fit). A venture capitalist, Andy Rachleff – also a lecturer of entrepreneurship at Stanford University (see, e.g., Saljoughian, 2017) – explains the importance of the market and team as follows:

• “When a great team meets a lousy market, market wins”.

• “When a lousy team meets a great market, market wins”.

• “When a great team meets a great market, something special happens”.

Quite often, a start-up runs out of cash before a scalable and profitable market–product fit is achieved. Finding an overall solution may require several pivots before a profitable, scalable and repeatable business model is found. Thus, financial management was reported to be a significant management challenge in start-ups (Foster & Davila, 2005). In addition, start-ups sometimes need to pivot, meaning that they have to change their strategic goals (Ries, 2010). Actually, of those start-ups that have succeeded, two-thirds were reported having drastically changed their plans along the way (Maurya, 2012). For example, Slack was born on the basis of an internal communication platform of a company that manufactures games. Twitter was originally founded as a subscription service for podcasts, and YouTube started as a dating site. These examples show that start-ups need to be able to learn from experiences by deeply reflecting on their experiences in order to create new meanings and understanding.

It is no wonder that for investors, the importance of the team is very important when making an investment decision. If the original business idea does not work, an excellent team is capable of both making a fast pivot and finding the right market–product fit. One of the critical qualities of a start-up team is their ability to fail fast and regroup their act on the basis of experience. Known as the “lean start-up” methodology, the aim is to supposedly eliminate wasted time and resources in order to develop a product iteratively and incrementally (Teece et al., 2016). However, the journey towards success using this approach also requires capital. Even an excellent team might not succeed after several rounds of funding.

2.6 Conceptual model for managing strategic learning

Successful management of a start-up requires structuring management approaches and adopting management systems and processes (Davila et al., 2010). However, this research finding does not mean bureaucracy or inflexible processes. Conversely, prior research (Anderson & Eshima, 2013) showed that entrepreneurially oriented established companies have performed better than companies that are more conservative in management culture and models. An entrepreneurially behaving company with a structured management approach is agile in terms of learning from customer behaviour and market development. Thus, its personnel focus on customers and markets in search of novel value and solution proposition, customers’ compelling reason to buy, and a replicable sales model.

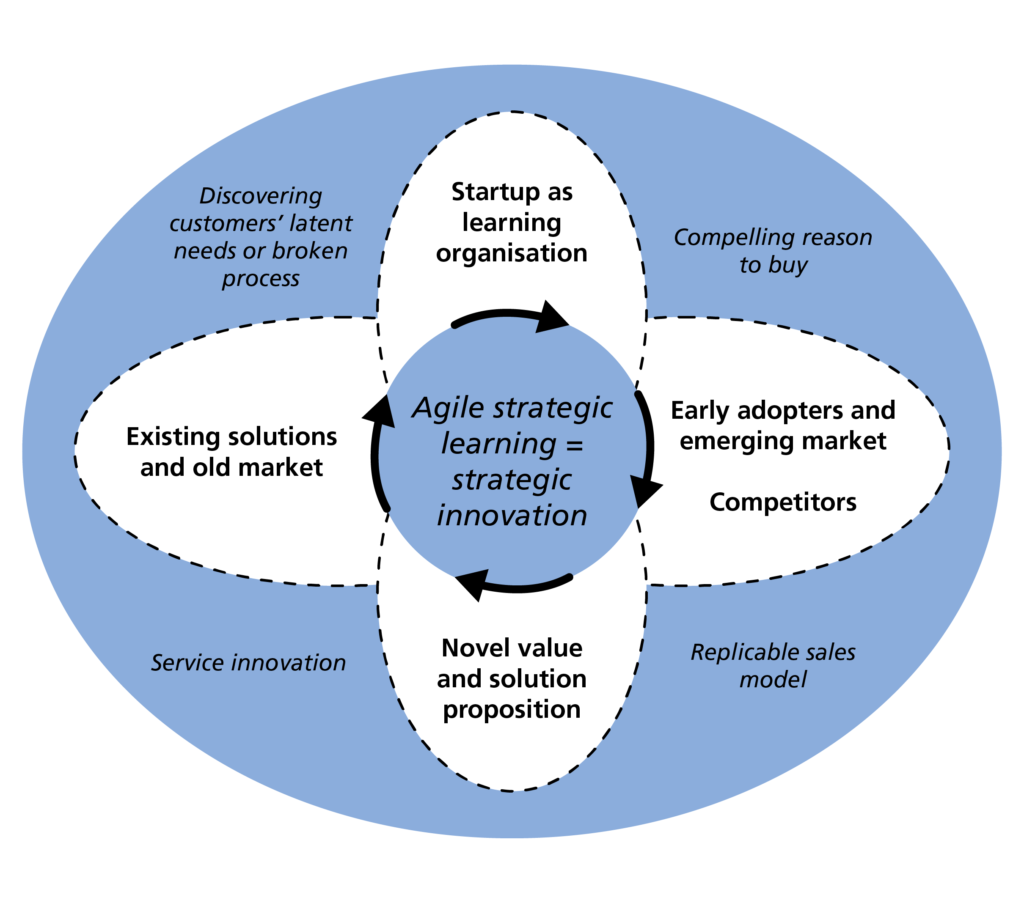

We summarized the literature findings in Figure 2. A start-up is a learning organization that needs to search for customer latent needs and the broken process in its early phases. By analysing the existing solutions and an existing market, start-ups learn about market opportunities for service innovations that fulfil the latent needs or fix the broken process. However, finding and defining customers’ compelling reason to buy and a replicable sales model, start-ups need to closely work with early adopters who represent the new customer segment of emerging markets. This finally assists them in finding novel value and solution proposition.

We have placed agile strategic learning in the middle of the model. Agile strategic learning is a business innovation process that takes a holistic perspective on start-up development. Its aim is to integrate the continuous market and customer study into concrete experimental learning where a start-up continually interacts with potential customers in innovating and designing new product or service innovations. Thus, it is more than product or service development. This is aligned with the studies of Beckman and Barry (2007) and Beckman (2020), who have shown that learning to innovate requires capabilities to combine abstract reflective thinking with concrete, experiential learning. Beckman (2020) used the concept of reframing by showing that existing thinking models should be questioned through abstract conceptualization and reflective observation.

Start-ups need to translate their observations and findings concerning customer behaviour and market changes into the actions of business development. This is an agile strategic learning and innovation process where start-ups reflect on their experiences with existing thinking models and reframe them in accordance with new market information. Beckman and Berry (2007) referred to experiential learning theories (e.g. Kolb et al., 2001) by stating that innovating something is a reflective learning process. It is especially about reframing one’s own thinking and expectations related to customer purchase behaviour, market development, and expectations of end users. In fact, Vygotsky (1978) has pointed out that, in the past, people developed many concepts and beliefs about several things that had a strong impact on their future learning situations and behaviours. Thus, agile strategic learning is a process in which start-up teams rapidly experiment with new things, aiming to learn and test existing beliefs and models.

3. Discussion

To respond our aims of this research, we examined how to manage a start-up experiencing a high level of uncertainty and the principles of continuous learning in a start-up. In this study, we addressed that continuous agile strategic learning by reframing one’s own thinking models related to customer behaviour and market plays a crucial role in start-up management. Learning in a start-up is a social process where teams collectively reflect on their existing product or service plans, marketing and sales models, and channel, partner, and pricing strategies for their experiences in emerging markets.

Unlike established companies, start-ups operate with novel products or services in emerging markets where customer understanding is limited and needs are immature. Thus, start-ups cannot create well-defined long-term strategic plans, as target markets do not yet exist. Start-ups usually have several rounds of informal strategy planning in a year, whereas established companies update their strategies according to the annual planning schedule once a year. Therefore, in this study, we stressed that the rate of learning is an essential strategic competitive advantage for start-ups. This is aligned with the conclusions of Kimura et al. (2019), who stated that competing on the rate of learning would become a necessity in every company.

The growth of a start-up is constantly confronted with external and internal forces of change, which require teamwork, preparedness, response, adaptation, and above all, through agile learning, reframing of existing thinking models and underlying assumptions. The journey of a start-up is often referred to as a roller coaster. During the same day, the team may experience both the peak moments and grating failures of success. Customer behaviour may change instantly as a new revolutionary competitor appears on the market, an important distribution channel changes radically, or a new technology platform breaks into the market. All of these have one thing in common that start-ups cannot control all of them. Thus, teams should focus on things they can control. The effectiveness of learning becomes the competitive asset to a start-up: how much a start-up learns new and how quickly it can apply what it has learnt as it adapts to a constant change. The capability to learn fast is becoming even more important than being in control of everything.

The logic of competition has changed from a predictable and stable competition to a complex and dynamic game that is played across many dimensions (Kimura et al., 2019). Consequently, similar to design, the continuous learning process in a start-up should follow the principles of continuous reframing through generative sensing, where there are no closed-set choices that are known a priori. Rather, in order to handle conflicting constraints and multidimensional interests and also potentially infinite number of solutions, the learning frame is generative, establishing either a broad initial objective or a small set of objectives (Dong et al. 2016). This also raises the question of whether or not the agile learning process of start-ups could be an applicable framework for solving wicked problems – next big things in emerging markets. According to Fahey (2016), John Camillus has noted that analysing and defining wicked problems actually requires taking action, namely hands-on experiments with rapid learning. In any case, the success of a start-up in today’s evermore competitive business environment requires that it must build novel solutions, which is something beyond the core.

On the contrary, changes within the start-up process also require continuous agile learning. How do the skills profiles of start-up teams change during a trip? Agile learning requires open collaboration between team members without the fear of managerial conflicts. Unlike in large corporations or public organizations, the performance and roles of each employee are very transparent in small start-ups. No one can shine only in meetings, because scarce resources must also be clearly allocated to productive work. The key is to find skillful people who adapt or are used to working on the principles of continuous learning.

4. Conclusions and future research

A start-up is the embodiment of a continuous race for resources, experiments, learning, networks, timing, and luck. Above all, we would like to emphasize the importance of continuous agile and strategic learning where start-up teams continuously reframe their existing thinking models in line with signals from emerging markets. Actually, this provides hints for start-ups in terms of how close or far they are in solving the wicked problem. Thus, as the speed of change is accelerating and the business environment is becoming both more competitive and complex, we suggest further research on applying the principles and practices of agile strategic learning in start-ups to wider entrepreneurial initiatives.

References

- Alamäki, A., Rantala, T., Valkokari, K., & Palomäki, K. (2018). Business roles in creating value from data in collaborative networks. In the proceedings of Pro-ve 2018, Working Conference on Virtual Enterprises (pp. 612–622). Springer, Cham.

- Aldrich, H. E., & Yang, T. (2014). How do entrepreneurs know what to do? Learning and organizing in new ventures. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 24(1), 59–82.

- Anderson, B. S., & Eshima, Y. (2013). The influence of firm age and intangible resources on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm growth among Japanese SMEs. Journal of business venturing, 28(3), 413–429.

- Assink, M. (2006). Inhibitors of disruptive innovation capability: a conceptual model. European journal of innovation management, 9(2), 215–233.

- Atalay, M., Anafarta, N., & Sarvan, F. (2013). The relationship between innovation and firm performance: An empirical evidence from Turkish automotive supplier industry. Procedia-social and behavioral sciences, 75(3), 226–235.

- Balfour, B. (2017). Building a Growth Framework Towards a $ 100 Million Product. Available: https://brianbalfour.com/essays/hubspot-growth-framework-100m

- Baltrūnaitė, V., & Sekliuckienė, J. (2020). The use of organizational learning practices in start-ups growth. Entrepreneurial business and economics review, 8(1), 71–89.

- Beckman, S. L., & Barry, M. (2007). Innovation as a learning process: Embedding design thinking. California management review, 50(1), 25–56.

- Beckman, S. L. (2020). To Frame or Reframe: Where Might Design Thinking Research Go Next?. California Management Review, 62(2), 144–162.

- Blank, S. (2020). The Four steps to the epiphany: Successful strategies for products that win, 5th edition. John Wiley & Sons.

- Cbinsights, (2020). 189 Of The Biggest, Costliest Startup Failures Of All Time. Research briefs, CBInsight, January 28, 2020. Available: https://www.cbinsights.com/research/biggest-startup-failures/

- Collis, D. J., & Rukstad, M. G. (2008). Can You Say What Your Strategy Is?. Harvard Business Review, April 2008, 1–10.

- Davila, A., Foster, G., & Jia, N. (2010). Building sustainable high-growth startup companies: Management systems as an accelerator. California Management Review, 52(3), 79–105.

- Doz, Y., & Kosonen, M., (2008). Nopea strategia: miten strateginen ketteryys auttaa pysymään kilpailun kärjessä. Talentum.

- Dong, A., Garbuio, M., Lovallo, D. (2016) Generative Sensing: A Design Perspective on the Microfoundations of Sensing Capabilities. California Management Review, 58(4), 103–104.

- Edison, H., Wang, X., & Abrahamsson, P. (2015, May). Lean startup: why large software companies should care. In Scientific Workshop Proceedings of the XP2015 (pp. 1–7).

- Fahey, L. (2016). John C. Camillus: discovering opportunities by exploring wicked problems. Strategy & Leadership, 44(5), 29–35.

- Frese, M., & Gielnik, M. M. (2014). The psychology of entrepreneurship. The Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 413–438.

- Foster, G., & Davila, T. (2005, July). Startup firms growth, management control systems adoption, and performance. In AAA Management Accounting Section 2006 Meeting Paper.

- Ghezzi, A., & Cavallo, A. (2018). Agile business model innovation in digital entrepreneurship: Lean startup approaches. Journal of business research, 110, 519–537.

- Hallikainen, H., Alamäki, A., & Laukkanen, T. (2019a). Lead users of business mobile services. International Journal of Information Management, 47, 283–292.

- Hallikainen, H., Alamäki, A., & Laukkanen, T. (2019b). Individual preferences of digital touchpoints: A latent class analysis. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 50, 386–393.

- Kimura, R., Reeves, M., Whitaker, K. (2019). The New Logic of Competition. BCG Henderson Institute Available: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2019/new-logic-of-competition

- Kolb, D. A., Boyatzis, R. E., & Mainemelis, C. (2001). Experiential learning theory: Previous research and new directions. Perspectives on thinking, learning, and cognitive styles, 1(8), 227–247.

- Koning, R., Hasan S., & Chatterji A. (2019). Experimentation and Startup Performance: Evidence from A/B Testing. HBS, August 2019.

- LinkedIn (2019). 3rd Annual Workplace Learning Report. Available: https://learning.linkedin.com/blog/learning-thought-leadership/2019-workplace-learning-report

- Maurya, A. (2012). Running Lean: Iterate from Plan A to a Plan That Works. 2nd Edition, O’Reilly Media Inc.

- Meredith, J. (1993). Theory building through conceptual methods. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 13(5), 3–11.

- Moore, G. A. (1991). Crossing the chasm: marketing and selling disruptive products to mainstream customers. Harper Collings Publisher.

- Paternoster, N., Giardino, C., Unterkalmsteiner, M., Gorschek, T., & Abrahamsson, P. (2014). Software development in startup companies: A systematic mapping study. Information and Software Technology, 56(10), 1200–1218.

- Ries E. (2010). The Lean Startup. How constant innovation creates radically successful businesses. Penguin Books.

- Rogers, E. M. (1995). Diffusion of innovations (4th ed.). Free Press.

- Roundy, P. T. (2018). Paying attention to the customer: consumer forces in small town entrepreneurial ecosystems. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 20(2), 323–340.

- Rosenbusch, N., Brinckmann, J., & Bausch, A. (2011). Is innovation always beneficial? A meta-analysis of the relationship between innovation and performance in SMEs. Journal of business Venturing, 26(4), 441–457.

- Ryan, C. (2016). Lean Business Planning vs. Traditional Approach. Business Modelling Blog. Available: http://centerforbusinessmodeling.com/lean-business-planning-vs-traditional-approach/

- Rumelt R. (2011). Good Strategy, Bad Strategy: the difference and why it matters. Profile Books cop.

- Saljoughian, P. (2017). 7 Lessons from Andy Rachleff on Product-Market Fit. Available: https://medium.com/parsa-vc/7-lessons-from-andy-rachleff-on-product-market-fit-9fc5eceb4432

- Sarooghi, H., Libaers, D., & Burkemper, A. (2015). Examining the relationship between creativity and innovation: A meta-analysis of organizational, cultural, and environmental factors. Journal of business venturing, 30(5), 714–731.

- Sekliuckiene, J., Vaitkiene, R., & Vainauskiene, V. (2018). Organisational learning in startup development and international growth. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 6(4), 125.

- Song, M., Podoynitsyna, K., Van Der Bij, H., & Halman, J. I. (2008). Success factors in new ventures: A meta‐analysis. Journal of product innovation management, 25(1), 7–27.

- Stam, W., Arzlanian, S., & Elfring, T. (2014). Social capital of entrepreneurs and small firm performance: A meta-analysis of contextual and methodological moderators. Journal of business venturing, 29(1), 152–173.

- Stirewalt, J. (2017). Clients need a compelling reason to buy. Available: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/clients-need-compelling-reason-buy-jim-stirewalt/

- Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic management journal, 28(13), 1319–1350.

- Teece, D, Peteraf, M., & Leih, S. (2016). Dynamic Capabilities and Organizational Agility: Risk, Uncertainty and Strategy in The Innovation Economy. California Management Review, Vol. 58, No. 4 Summer 2016.

- Tjan, A. (2012). Great businesses don’t start with a plan. Harvard Business Review. Available: https://hbr.org/2012/05/great-businesses-dont-start-wi

- Toft-Kehler, R., Wennberg, K., & Kim, P. H. (2014). Practice makes perfect: Entrepreneurial-experience curves and venture performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(4), 453–470.

- Uotila, T. P. (2015). Exploring the CEOs’ Performance Cognitions. In the proceedings of European Conference on Knowledge Management, (pp. 983–990) Kidmore End, Academic Conferences International Limited.

- Valkokari, K., Rantala, T., Alamäki, A., & Palomäki, K. (2018). Business impacts of technology disruption – a design science approach to cognitive systems’ adoption within collaborative networks. In the proceedings of Pro-ve 2018, Working Conference on Virtual Enterprises (pp. 337–348). Springer, Cham.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- York, J. L., & Danes, J. E. (2014). Customer development, innovation, and decision-making biases in the lean startup. Journal of small business strategy, 24(2), 21–40.

- Wood, W. & Li, S. (2005). The empirical analysis of technology camel. Issues in Information Systems, 6(2), 154–160.