Abstract

Self-efficacy is a person’s belief in one’s own competencies in dealing with difficult and uncertain tasks and difficulties with special needs. Previous research showed that as people’s self-efficacy beliefs increase, behavior change also increases. Self-efficacy can be seen as an explanatory factor of the high performance that people should show in entrepreneurship processes. The aim of this research is to determine the impact of self-efficacy on entrepreneurship performance. This is an empirically designed research. Survey data were collected from 296 randomly selected respondents who started up his or her own actively running businesses in Konya province in Turkey. Data were analyzed by using exploratory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, and structural equation modeling path analysis techniques. The findings of this research indicate that self-efficacy has a positive impact on entrepreneurship performance. Results suggest that self-efficacy is a robust predictor of the source of entrepreneurship performance of the people. Thus, great emphasis should be given for increasing the self-efficacy of entrepreneurs.

Keywords: self-efficacy, entrepreneurship performance, entrepreneur

Introduction

The personal view an individual holds of his/her capabilities in successfully completing an undertaking plays an important role in the process of making decisions whether or not to take on new challenges, which may entail coping with obstacles and require perseverance and determination in the face of hindrances (Mauer et al., 2017; McGee & Peterson, 2019). Throughout his/her lifespan, indications of the perception of self-efficacy can be traced in an individual’s performance when choosing to initiate an action and persist on it (Boyd & Vozikis, 1994). More specifically, an individual with high-level self-efficacy is more likely to exhibit initiation behavior, effort, and unwavering determination (McGee & Peterson, 2019).

The construct of self-efficacy is considered to be a determinant factor in mobilizing an individual in the direction of venturing into a new business (Gielnik et al., 2020). More precisely, when one holds higher levels of self-efficacy s/he can highly likely to succeed in the intended undertaking. Self-efficacy more reliably indicates future accomplishments than past records of successes (Chen et al., 1998). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy is used to define an individual’s confidence in his/her abilities, and has a determinant role in shaping entrepreneurial intentions (Li-Yu & Jian-Hao, 2019). In this respect, it can be assumed that the level of entrepreneurial self-efficacy correlates with entrepreneurial intentions (Drnovšek et al., 2010).

The studies in the literature indicate that there exists a strong link between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and the performance of a company started by an entrepreneur. However, there is still a need to investigate this relationship empirically in a country-specific context. Studies have generally been conducted in the western culture, and the cultural environment of the society might have effects on self-efficacy and the entrepreneur’s firm performance (Naktiyok, Karabey, & Gulluce, 2010). Thus, this research aimed to bring a new perspective to the scientific discussion in a Turkish context. In this paper first, the theoretical background to the both construct of self-efficacy and the entrepreneur’s firm performance was discussed. Then findings, results, and implications of the research were given.

1. Theorethical framework

1.1 Self-Efficacy

The foundations for the theory of self-efficacy were laid within the framework of locus of control theory by Rotter (1954) and attribution theory by Heider (1944). Self-efficacy is defined as a person’s belief in his or her capability to perform a given task or courses of action needed to exercise control over events in their lives (Bandura, 1994; Boyd & Vozikis, 1994; Chen et al., 1998; Hmieleski & Corbett, 2008; Pajares, 1997). It indicates whether an individual can imagine him/herself attaining the goals set and exhibit the personal qualities required for the completion of that goal (Gallagher, 2012). It is about one’s belief in his ability to activate motivational, cognitive and functional abilities in a given circumstance (Wood & Bandura, 1989).

The personal evaluation of past experiences contributes to how one perceives his/her self-efficacy. The question of whether an individual can perceive her/himself as successfully coping with challenges in her/his future undertakings indicates self-efficacy (Mauer et al., 2017). When an individual holds higher levels of self-efficacy, the likelihood of him venturing into new courses of action for the attainment of a goal is expected to increase. The entrepreneurial spirit is expected to be higher for those individuals with efficacious outlook on his/her potential to act (Drnovšek et al., 2010). It is that kind of attitude which would play an important role for the successful completion of the entrepreneurial undertaking.

Individuals who exhibit higher levels of self-efficacy feeling are likely to readily accept and embark on undertakings that potentially involve challenges in the process of implementing them (Bandura, 1994). They remain steadfast in their commitment to succeed in their goals regardless of the potential failures and resilient enough to get back to their original stance when failures or setbacks occur (Hmieleski & Corbett, 2008).

An individual gradually attains a high level of self-efficacy through time as s/he experiences accomplishments and successfully deals with problems through effort and persistence, which ultimately helps him/her develop a belief in his/her capabilities to successfully invest in motivational and cognitive resources needed (Mauer et al., 2017). Individuals usually avoid engaging in actions in which they expect to have low control and prefer situations with high personal control (Chen et al., 1998). High-level self-efficacy usually comes after the success of an individual experience in an action undertaken that previously involved uncertainties. The sheer experience of success in such uncertain situations helps an individual build a robust belief in self-efficacy (Bandura, 1994).

Self-efficacy beliefs influence behavior through four mediating processes: goal-setting and persistence, affect, cognition, and selection of environments and activities (Bandura, 1994). The influence of self-efficacy can be observed in the selection of goals, goal-oriented actions, effort invested in the process, and determination to succeed despite difficulties. Individuals holding a strong sense of self-efficacy tend to invest more effort in the process to cope with challenges they faced. The sense of self-efficacy greatly influences the ways in which individuals respond to life events, which ultimately affect cognition and action. It also bears heavily on the type and intensity of the effect (Bandura, 1993). An individual’s beliefs about self-efficacy greatly shape type of the goals set and the plans and strategies devised to obtain those goals. It further shapes the development of rules for predicting and influencing events as well as efficiency in solving problems. In situations where individuals have to make sound decisions about whether to engage in a tough task, those who are holding beliefs in their problem-solving abilities, eventually, prove themselves as efficient decision-makers and problem solvers. Individuals tend to prefer engaging in situations in which they expect to accomplish well and avoid situations in which they anticipate that the demands placed on them are likely to overtax their abilities. Apparently, that self-efficacy beliefs greatly influence individuals’ preferences for engaging in situations and activities (Maddux, 1995).

The construct of self-efficacy attempts to explain processes influencing the execution of an action rather than the outcome of the action. It is defined in terms of one’s self-assessment of own abilities to perform according to the requirements of a set goal (Liu et al., 2017; Maddux, 1995). Self-efficacy does not necessarily indicate a usual behavior pattern but rather it defines a certain behavior pattern for a particular activity. It should be noted here that having self-efficacy belief in distinct domains has a positive influence on the self-efficacy belief for new situations. Accordingly, the belief in one’s abilities to cope with challenging situations, convictions for success, and past accomplishments all contributes to self-efficacy (Kulviwat et al., 2014).

According to social cognitive theory, nature of interrelationship among cognition, behavior, and situational events is dynamic and has wider implications in the long run. Social cognitive theory suggests that humans have a capacity for using symbolic cognitive activity. (Wang et al., 2019). This quality of human cognition may explain why humans in advance can visualize possible situations/events, possible emotional and behavioral responses to those situations as well as possible outcomes of their conducts in those situations. Using his/her power of imagination an individual can visualize him/herself as un/successfully dealing with the demands of a possible situation in the future and accordingly form beliefs about her/his own self-efficacy. Similarly, actual experiences or vicarious experiences may form the basis for mental scenarios imagined. However, the actual success or failure experiences influence self-efficacy more than vicarious experiences (Maddux, 1995).

Accomplishments in the past contribute positively to one’s level of self-efficacy while repeated failures lead to lower levels of self-efficacy. Failures negatively affect one’s belief in his abilities and prevent him from performing efficiently (Yıldırım & İlhan, 2010). Yet, accomplishments in the past will help boost one’s belief in self-efficacy and foster success in the future. Having certain abilities to accomplish intended goals is not the sole factor. To put it differently, one’s abilities mediate between his belief in self-efficacy and accomplishment of intended goals. Ultimately, this situation is expected to bring an increase in the tendency for venturing. From this interrelationship, it can be concluded that self-efficacy does not necessarily indicate one’s ability but rather his belief in existing resources (Akkoyunlu et al., 2005). The sources of one’s perception of self-efficacy can be traced back to the resilience and responses they develop when he or she sets goals and attempts to succeed in it even in the face of challenges. Hence, it can be said that as the perception of self-efficacy increases, the number of goals and efforts invested to reach those goals also increases (Çetin & Basım, 2010).

1.2 Entrepreneurship Performance

Most courses of action are initially organized in thought. The perception of self-efficacy greatly affects the process of forming anticipatory scenarios and acting them out in the mind. Individuals with a high level of self-efficacy are expected to set goals involving many challenges and remained determined to accomplish their goals throughout the process. They usually visualize success scenarios, which offer them a framework for the optimum course of action and performance (Bandura, 1994).

Career development theory provides a framework that attempts to examine the role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions and behaviors. It suggests that the level of entrepreneurial self-efficacy at the onset of the career development process has implications on one’s entrepreneurial intentions (Zhao et al., 2005). Also, job experiences one gets in the past shape self-efficacy beliefs through successfully completed feats that require mastery in that area. In regard, it should also be noted that individuals may initially hold entrepreneurial intentions but wait till they reach the level of confidence at which they can expect to succeed in their new business venture. Yet, that type of confidence is gained in the process of enactive mastery. On the other hand, some individuals who are in later stages of career development usually feel the need to realize career growth when they find themselves pushed out of the job market and got unemployed (Boyd & Vozikis, 1994).

Positive consequences of an individual’s actions are expected to boost his/her self-efficacy, while negative ones are expected to lower (Pajares, 1997). If people experience only easy successes, they come to expect quick results and are easily discouraged by failure. A resilient sense of efficacy requires experience in overcoming obstacles through perseverant effort and that may result in a mastery experience (Boyd & Vozikis, 1994; Mauer et al., 2017). Challenges and demanding situations experienced in the process of attaining goals lead to the recognition that success comes from perseverance. Once an individual starts to become aware of his/her potential to succeed, s/he is more likely to endure hardships and quickly recover from failed attempts. The very experience of enduring in the face of challenges would make him/her stronger and more resilient (Bandura, 1994).

The impact of modeling on perceived self-efficacy is strongly influenced by perceived similarity to the models. The greater the assumed similarity, the more persuasive are the models’ successes and failures. We learn through modeling or repeating the behavior of others, that is also called vicarious experience (Bandura, 1994; Mauer et al., 2017).

People seek proficient models who possess the competencies to which they aspire (Bernard et al., 2011). Vicarious experience occurs when a certain social behavior, e.g., entrepreneurship, is informally observed and then adopted by an individual. Hence, the learning occurs by example rather than by direct experience. Proficient role models convey effective strategies for managing situations, and they affect self-efficacy through a social comparison process. That is, people form judgments of their own capabilities by comparing themselves to others (Boyd & Vozikis, 1994).

Presence of a high-performing parent entrepreneur has a positive impact on an individual’s choice of an entrepreneurial career (Rocha & Van Praag, 2020). However, role models do not necessarily have to be actual entrepreneurs or parents although they can be, but a role model always has to be relevant and believable for the situation in which the individual finds himself or herself in. Many of the functions of the mentor relationship may increase entrepreneurial self-efficacy (Boyd & Vozikis, 1994; Mauer et al., 2017).

Social persuasion strengthens people’s beliefs that they have what it takes to succeed. People who are persuaded verbally that they possess the capabilities to master given activities are likely to mobilize greater effort and sustain it than if they harbor self-doubts and dwell on personal deficiencies when problems arise (Bandura, 1994). It is also a possibility that social persuasion may increase self-efficacy beliefs to unrealistic levels. Therefore, social persuasion should incorporate the assignment of tasks that develop self-improvement (mastery experiences) in order to ensure success (Bandura, 2012). In addition, it is important to consider such factors as the credibility, expertise, trustworthiness, and prestige of the persuading person when evaluating the usefulness of persuasive information. Persuaders can play an important part in the development of an individual’s self-beliefs (Pajares, 1997). If the source of social support is a trusted and successful role model to the individual, verbal persuasion may exert an even more profound influence on the development of entrepreneurial self-efficacy (Boyd & Vozikis, 1994).

The relationship between self-efficacy and performance has direct implications for the development of entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Activities and environments are selected by people based on their judgments or perceptions of personal self-efficacy. Activities and situations that are viewed as exceeding their coping abilities are avoided in favor of situations they judge themselves capable of managing. If a person experiences past success on the job may experience greater levels of self-efficacy when faced with similar circumstances in new situations. This individual may set higher personal goals, may be more persistent in overcoming obstacles, and perform better in the long run (Boyd & Vozikis, 1994).

Self-efficacy beliefs help to determine how much effort people will expend on an activity, how long they will persevere when confronting obstacles, and how resilient they will prove in the face of adverse situations – the higher the sense of efficacy, the greater the effort, persistence, and resilience. Self-efficacy beliefs are strong determinants and predictors of the level of accomplishment that individuals finally attain (Pajares, 1997).

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy is an individual’s belief in his or her ability to achieve various entrepreneurial tasks (Chen et al., 1998; Miao at al., 2017). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy affects entrepreneurial career choice and development (Chen et al., 1998). In stable environments, where decision options are more certain due to higher levels of transparency and predictability, overconfidence is less likely to occur. Highly optimistic entrepreneurs who are also high in entrepreneurial self-efficacy will be more successful. This is because the environment is more likely to be in alignment with their past experience, thus reducing the need to consider various decision options in detail. Therefore, they should be able to draw on their confidence in their abilities to move forward to make quick decisions with less negative consequences, because decision alternatives will be more transparent to them in stable environments as compared to dynamic ones (Hmieleski & Baron, 2008).

As entrepreneurs hold strong beliefs in their own abilities to accomplish tasks in entrepreneurial areas, they establish challenging goals, display persistence, invest efforts regarding entrepreneurial tasks, and recover rapidly from failure. The effects of these invested efforts are reflected in performance (Miao et al., 2017).

Performance is both outcome and determinant of self-efficacy. Individuals become more confident after the successful completion of various tasks so it is likely that an entrepreneur’s confidence in their ability to develop their business likely improves as the firms experience sustained success (Chen et al., 1998; McGee & Peterson, 2019). Likewise, altering a new venture’s entrepreneurial orientation to better meet the needs of an evolving marketplace may produce long-term performance benefits. Entrepreneurial orientation’s relationship with performance likely changes over time because entrepreneurs learn what types of firm behavior or strategic posture is most appropriate (McGee & Peterson, 2019).

1.3 Research Hypothesis

Triadic reciprocal determinism indicates that individual, environmental, and behavioral factors are independent from but interact with one another (Zhao et al., 2020). The effect of environmental factors on behavioral factors is latent and becomes substantial only when environmental factors are combined with individual factors and triggered by corresponding behaviors. Moreover, individual and environmental factors are reciprocally determined by each other, and environmental factors positively affect individual factors (Li-Yu & Jian-Hao, 2019).

There is a robust positive relationship between self-efficacy and performance (Hechavarria et al.,, 2012; Hmieleski & Corbett, 2008). Individuals start new businesses primarily for intrinsic reasons, as opposed to extrinsic rewards. Work satisfaction may be an even more important indicator of success for individual entrepreneurs than financial performance. After all, money is only a means through which one may potentially use in the pursuit of finding satisfaction. Lack of money is sure to reduce satisfaction if one’s basic needs cannot be met, but excess amounts of money will not guarantee happiness (Hmieleski & Corbett, 2008).

Self-beliefs of efficacy play a key role in the self-regulation of motivation. People tend to form beliefs about what they can do. They anticipate likely outcomes of prospective actions. They set goals for themselves and plan courses of action designed to realize valued futures. There are three different forms of cognitive motivators: causal attributions, outcome expectancies, and cognized goals. The corresponding theories are attribution theory, expectancy-value theory and goal theory, respectively. Self-efficacy beliefs influence causal attributions, likely outcomes of performance, and cognitive mechanism of motivation. Explicit, challenging goals enhance and sustain motivation. Those who have a strong belief in their capabilities exert greater effort when they fail to master the challenge. Strong perseverance contributes to performance accomplishments (Bandura, 1994).

Self-efficacy influences personal goal setting and goal commitment. People who perceive a high sense of self-efficacy set more challenging goals for themselves and possess a stronger commitment to these goals. These individuals are also more likely to construct or visualize success scenarios that guide performance than people who are low in self-efficacy (Boyd & Vozikis, 1994). The higher the level of people’s perceived self-efficacy the wider the range of career options they seriously consider, the greater their interest in them, and the better they prepare themselves for the occupational pursuits they choose and the greater is their success (Bandura, 1994).

There are enough studies that statistically proven the relationship between self-efficacy and entrepreneurship performance. However, this relationship deserves investigation because the national infrastructure and culture might play notable role in this relationship. For instance, while in the western culture individualism is high and uncertainty avoidance is low, in Turkey collectivism and uncertainty avoidance are high (Naktiyok et al., 2010). Additionally, the literature on exploring this relationship by considering cultural differences is limited. Similarly, such types of researches in the Turkish context are also scarce. Thus, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H: There is a positive impact of self-efficacy on entrepreneurship performance in the context of Turkish culture.

2. Research Method

The purpose of this research was to examine the relationship between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurship performance. This research was designed quantitatively to find out a generalized pattern of this relationship in the context of Turkey. A questionnaire with three parts was formed to collect primary data. The first part of the questionnaire measured “entrepreneurial self-efficacy”, the second part measured “entrepreneurship performance” and the third part investigated demographic characteristics of participants. Both measures, self-efficacy and entrepreneurship performance, were 5-point Linkert scales ranged from “1 = strongly disagree ” to “5 = strongly agree”.

The measures for the entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurship performance were taken from the study of Buang (2012). The measures were translated and validated in Turkish language by Abdullahi (2017, pp. 32-33). The entrepreneurial self-efficacy measure consisted of 29 items and entrepreneurship performance consisted of 21 items. Cronbach’s Alpha reliability coefficients for internal consistency of the measures “entrepreneurial self-efficacy” and “entrepreneurship performance” were 0.80 and 0.76 respectively. Results of the reliability tests suggested that the internal consistency of the items of the measures were good.

Population of the research was people working in organizations, mainly entrepreneurs, in the province of Konya, in Turkey. Konya is one of the top 5 developed big cities in Turkey. A total of 400 questionnaires were delivered to randomly selected firms, 322 (81%) questionnaires were returned and 296 questionnaires were scrutinized valid for analysis. To see a clear picture of the current situation and to get a general idea about the entrepreneurship performance level, no specific target business group was focused on. When considering the techniques used in the data analysis method it was estimated that the sample size was adequate (Hox & Bechger, 2006). Exploratory Factor Analysis, Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modelling techniques were employed for data analysis.

The questionnaire was first submitted to six practitioners and researchers who were expert in the field of research subject to maintain surface validity. Then, a pilot study was carried out with 40 valid responses to test the preliminary validity of the measures. In the course of analyzing the pilot data, to clarify the understanding of the measure items more, some items were rephrased.

2.1 Demographics

Finding of the descriptive statistics for the demographic characteristics revealed that majority of the respondents were male (97.64%), married (72.97%), in the age group of 36 to 50 years (36.82%), and hold High School and above degrees (54.05%). Most of the participants had 7 to 9 years work experience (25.68%) in their existing organizations. It was observed that majority of participants work at production department (61.15%) at the status of worker. The firms, where the respondents are currently working, are mainly small scaled organizations (78.72%) operating more than 20 years (19.26%) in food and beverage sector (13.85%). More than half of the respondent had experience of started-up of a business (55.74%), and actively owned at least one start-up (56.76%).

2.2 Explanatory Factor Analysis for the Measures

Exploratory factor analysis enables to regroup variables into a limited set of clusters based on shared variance (Bartholomew et al., 2011; Yong & Pearce, 2013). An exploratory factor analysis was conducted for the measure of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Kaiser-Meyer Olkin (KMO) measures adequacy of the sample and it is used to contrast between the extents and the scales of the observed correlation coefficients in relation to the extents of the partial correlation coefficients. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy suggested that the sample was factorable (KMO= 0.69). The KMO value indicates that the variables are related to each other, share common factor and are patterned relationships between the items (Bartholomew et al., 2011). The Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity tests the hypothesis that the correlation matrix is equal to the unit matrices. It had a statistically significant result (χ2 = 721.157, df = 136, p <000). After determining that the factor analysis for the entrepreneurial self-efficacy structure can be applied, factor analysis based on the “Varimax” rotation with Principal Component Analysis method was performed. Twelve items of the measure generated low loading or close loading in more than one component simultaneously. Therefore, these items were dropped from the analysis. Exploratory factor analysis generated six dimensions for the measure of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. These dimensions explained 57.03% of total variance. Since one component got only two items, this component combined with the close concept covering component. One component was disregarded since Cronbach’s Alpha of this component was below the accepted threshold. Further analysis conducted with the compound variables named persistence, affect, selection, and goal-setting.

An exploratory factor analysis was conducted for the measure of entrepreneurship performance. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy suggested that the sample was factorable (KMO = 0.714). The Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity test had a significant result (χ2 = 839.634, df = 210, p <000), indicating that the factor analysis for the entrepreneurship performance structure can be applied. Explanatory Factor Analysis based on the “Varimax” rotation with Principal Component Analysis method was performed. An item of the measure was eliminated from the analysis. Exploratory factor analysis generated seven dimensions for the measure of entrepreneurship performance. These dimensions explained 54.79% of total variance. Two components got only two items each. These components combined with the other close components. One component was disregarded since Cronbach’s Alpha of this component was below the accepted threshold. Further analysis conducted with the compound variables named patience, revenue, growth, and opportunity.

2.3 Covariance Analysis

Covariance analysis is used to minimize the error variance, increases the strength of the model, and removes the systematic error which could affect the results (Burgazoğlu, 2013, p. 19). It also clarifies the differences between the results of certain characteristics of groups. As depicted in Table 1, covariance among the variables were significantly correlated, and strength of the correlation among the variables were mostly high.

2.4 Structural Equation Modelling

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Persistence | 296 | 3.277 | 0.924 | 1 | |||||||

| Affect | 296 | 3.521 | 0.813 | 0.166** | 1 | ||||||

| Selection | 296 | 3.455 | 0.776 | 0.297** | 0.149* | 1 | |||||

| Goal-Setting | 296 | 3.439 | 0.651 | 0.274** | 0.267** | 0.337** | 1 | ||||

| Patience | 296 | 3.472 | 0.604 | 0.295** | 0.482** | 0.243** | 0.232** | 1 | |||

| Revenue | 296 | 3.214 | 0.923 | 0.888** | 0.150** | 0.258** | 0.271** | 0.295** | 1 | ||

| Growth | 296 | 3.399 | 0.817 | 0.166** | 0.241** | 0.275** | 0.743** | 0.226** | 0.168** | 1 | |

| Opportunity | 296 | 3.437 | 0.571 | 0.329** | 0.280** | 0.328** | 0.378** | 0.392** | 0.322** | 0.325** | 1 |

Structural equation modelling (SEM) is a multivariate analysis technique to determine the strength of relationships among constructs. The main application of SEM is path analysis, which hypothesizes between variables and tests the models with linear equation (Liu & Hsiang, 2015, p. 784). Fit indices are used to determine the fitness of the model in SEM (Walker & Maddan, 2013).

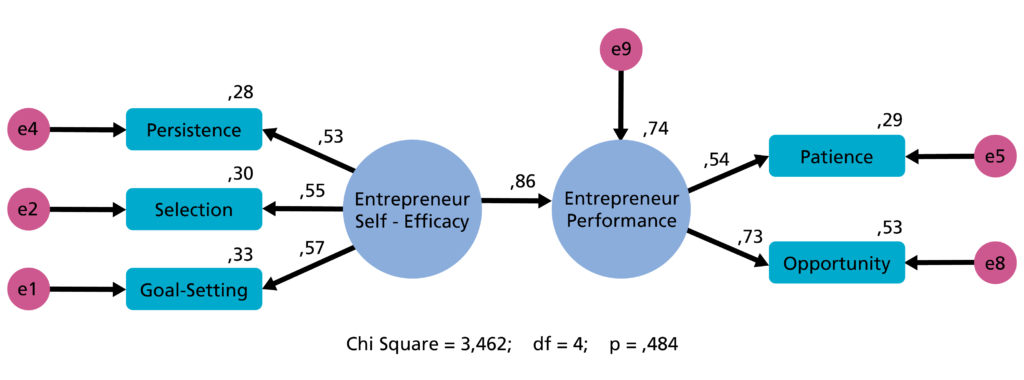

Figure 1 displays SEM results with standardized values. SEM results for the exogenous construct entrepreneurial self-efficacy contained three components, namely; persistence, selection and goal-setting. The endogenous construct entrepreneurship performance consisted of two components: patience and opportunity. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was executed for both constructs. Results of CFA analysis suggested to drop “affect” component of the exogenous construct and “revenue” and “growth” components of the endogenous construct. SEM model yielded statistically fit indices [χ2 = 3.462 (4), p 0.484; GFI = 0.995; AGFI; 0.982; RMSEA = 0.000] and found a robust positive relationship between the variables entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurship performance (R2 = 0.74, p < 0.001). The proposed hypothesis (H1: β = .860, p < 0.001) was supported.

Conclusion and Suggestions

This research was focused on the relationship between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurship performance. It was observed that both concepts, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurship performance, were examined by scholars. However, there is limited research exploring this relationship in the context of Turkish culture.

The results of this research are in parallel with the previous researches. Findings of this research also proved that there is a strong relationship between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurship performance in the context of Turkish context as well. In other words, one of the most important determinants of entrepreneurship performance is entrepreneurial self-efficacy.

Since entrepreneurial self-efficacy is a dominant predictor for entrepreneurship performance, a strong emphasis should be given on this subject. Research results suggest that if an individual has a high sense of self-efficacy, he or she will have higher entrepreneurial success. Individuals with higher entrepreneurial self-efficacy are more confident in their ability to run their own business with high performance. When people motivated, encouraged, supported, and directed to become an entrepreneur and run their own business, their self-efficacy becomes high, and their desire to attain goals, even under hard obstacles, increases. Therefore, people ought to be trained, motivated, and supported to become entrepreneurs.

This research has its own limitations that offers further research opportunities. The data in the survey was collected via self-reported measures from the participants. Further researches can be carried qualitatively to get deeper knowledge of the concept. Secondly, the present study was carried out in Turkey. Similar research can be conducted in other regions or countries to find out the effect of cultural differences.

References

- Abdullahi, S. M. (2017). Impact of individual factors on entrepreneurship: Comparison of inexperienced and senior entrepreneurs. (Master Thesis), Selcuk University, Konya, Turkey. Retrieved from https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi (492974)

- Akkoyunlu, B., Orhan, F., & Aysun, U. (2005). Bilgisayar Öğretmenleri için” Bilgisayar Öğretmenliği Öz-Yeterlik Ölçeği” Geliştirme Çalişmasi. Hacettepe Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 29(29), 1–8.

- Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational psychologist, 28(2), 117–148.

- Bandura, A. (1994). Self-Efficacy. In V. S. Ramachandran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Human Behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 71–81). Academic Press.

- Bandura, A. (2012). On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. Journal of Management, 38(1), 9–44.

- Bartholomew, D. J., Knott, M., & Moustaki, I. (2011). Latent variable models and factor analysis: A unified approach (Vol. 904). John Wiley & Sons.

- Bernard, T., Dercon, S., & Taffesse, A. S. (2011). Beyond fatalism-an empirical exploration of self-efficacy and aspirations failure in Ethiopia.

- Boyd, N. G., & Vozikis, G. S. (1994). The influence of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 18(4), 63–77.

- Buang, N. A. (2012). Entrepreneurs’ Resilience Measurement. Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

- Burgazoğlu, H. (2013). Çok Değişkenli Kovaryans Analizi ve 360 Derece Performans Değerlendirmesi Üzerine Bir Uygulama. (Master Thesis), İstanbul Üniversitesi, İstanbul

- Chen, C. C., Greene, P. G., & Crick, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 295–316.

- Çetin, F., & Basım, H. (2010). İzlenim yönetimi taktiklerinde öz yeterlilik algısının rolü. Erciyes Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Dergisi(35), 255–269.

- Drnovšek, M., Wincent, J., & Cardon, M. S. (2010). Entrepreneurial self‐efficacy and business start‐up: developing a multi‐dimensional definition. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 16(4), 329–348.

- Gallagher, M. W. (2012). Self-Efficacy. In V. S. Ramachandran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Human Behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 1957-1963). Elsevier Inc.

- Gielnik, M. M., Bledow, R., & Stark, M. S. (2020). A dynamic account of self-efficacy in entrepreneurship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(5), 487.

- Hechavarria, D. M., Renko, M., & Matthews, C. H. (2012). The nascent entrepreneurship hub: goals, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and start-up outcomes. Small Business Economics, 39(3), 685–701.

- Heider, F. (1944). Social perception and phenomenal causality. Psychological Review, 51(6), 358.

- Hmieleski, K. M., & Baron, R. A. (2008). When does entrepreneurial self‐efficacy enhance versus reduce firm performance? Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 2(1), 57–72.

- Hmieleski, K. M., & Corbett, A. C. (2008). The contrasting interaction effects of improvisational behavior with entrepreneurial self-efficacy on new venture performance and entrepreneur work satisfaction. Journal of Business Venturing, 23(4), 482–496.

- Hox, J. J., & Bechger, T. M. (2006). An Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling. Family Science Review, 354–373.

- Kulviwat, S., Bruner II, G. C., & Neelankavil, J. P. (2014). Self-efficacy as an antecedent of cognition and affect in technology acceptance. Journal of Consumer Marketing.

- Li-Yu, W., & Jian-Hao, H. (2019). Effect of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy on the Entrepreneurial Intentions of Students at a University in Hainan Province in China: Taking Social Support as a Moderator. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 18(9).

- Liu, J., Cho, S., & Putra, E. D. (2017). The moderating effect of self-efficacy and gender on work engagement for restaurant employees in the United States. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(1), 624–642.

- Liu, M. M. R. M., & Hsiang, S. M. (2015). Planning for uncertainty: use of structural equation modelling to determine the causal structure of time buffer allocation. Construction Management and Economics, 33(10), 783–798.

- Maddux, J. E. (1995). Self-Efficacy Theory. In J. E. Maddux (Ed.), Self-Efficacy, Adaptation, and Adjustment: Theory, Research, and Application (pp. 3–33). Springer US.

- Mauer, R., Neergaard, H., & Linstad, A. K. (2017). Self-efficacy: Conditioning the entrepreneurial mindset. In Revisiting the entrepreneurial mind (pp. 293–317): Springer.

- McGee, J. E., & Peterson, M. (2019). The long‐term impact of entrepreneurial self‐efficacy and entrepreneurial orientation on venture performance. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(3), 720–737.

- Miao, C., Qian, S., & Ma, D. (2017). The relationship between entrepreneurial self‐efficacy and firm performance: a meta‐analysis of main and moderator effects. Journal of Small Business Management, 55(1), 87–107.

- Naktiyok, A., Karabey, C. N., & Gulluce, A. C. (2010). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention: the Turkish case. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 6(4), 419–435.

- Pajares, F. (1997). Current directions in self-efficacy research. Advances in motivation and achievement, 10(149), 1–49.

- Rocha, V., & Van Praag, M. (2020). Mind the gap: The role of gender in entrepreneurial career choice and social influence by founders. Strategic management journal, 41(5), 841–866.

- Rotter, J. B. (1954). Social learning and clinical psychology: Johnson Reprint Corporation.

- Walker, J. T., & Maddan, S. (2013). Statistics in Criminology and Criminal Justice: Analysis and Interpretation (4th Ed.): Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Wang, S., Hung, K., & Huang, W.-J. (2019). Motivations for entrepreneurship in the tourism and hospitality sector: A social cognitive theory perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 78, 78–88.

- Wood, R., & Bandura, A. (1989). Impact of conceptions of ability on self-regulatory mechanisms and complex decision making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(3), 407.

- Yıldırım, F., & İlhan, İ. Ö. (2010). Genel öz yeterlilik ölçeği türkçe formunun geçerlilik ve güvenilirlik çalışması. Turk Psikiyatri Dergisi, 21(4), 301–308.

- Yong, A. G., & Pearce, S. (2013). A Beginner’s Guide to Factor Analysis: Focusing on Exploratory Factor Analysis. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 9(2), 79–94.

- Zhao, H., Seibert, S. E., & Hills, G. E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1265.

- Zhao, Y., Lin, S., & Liu, J. (2020). Employee innovative performance in science and technology-based small and medium-sized enterprises: A triadic reciprocal determinism perspective. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 48(11), 1–17.